"Hearing Raggamuffin Hip-hop: Musical Records as Historical Record," by Wayne Marshall and Pacey Foster

To celebrate the upcoming release of Ethnomusicology Review Volume 18, we're teaming up with the IASPM-US website for a co-edited series on the broad topic of Ethnomusicology and Popular Music. We're excited to kick off the series with a mixtape and historical survey of raggamuffin hip-hop, by technomusicologist Wayne Marshall and rap archaeologist Pacey Foster. This piece is being cross-listed at the website for the International Association for the Study of Popular Music, US Branch, and a complementary article has simultaneously been published at The Cluster Mag.

Born of reggae’s and hip-hop’s shared roots, shared sensibilities, and -- crucially -- shared spaces, raggamuffin hip-hop is a sound that emerged in the late 80s in places where large numbers of Jamaican youngsters encountered a dominant black youth culture in thrall to hip-hop -- and vice versa. As drug-running posses and US media refigured Jamaicans from off-the-boat country bwoys into ruthless badman aliens, the rising currency of reggae made a distinctive battery of sonic weapons -- honed at countless sound clashes and mic-passing sessions in Jamaica -- into potent signs in New York City.

Raggamuffin hip-hop is a public record of young people working to rock the mic and rock the party in transnational multiculture. In the late 80s and early 90s, one version of consummate cool-and-deadly style called for code-switching, flip-tongue fluency over neck-snapping, boom-bapping beats. With its dusty funk drums crunched by bit-constrained machines, bass pushed into the red, and gravelly voices booming sound system stylee, raggamuffin hip-hop embodies a particular kind of New York grit.

The production of raggamuffin hip-hop records, especially during the period we focus on (1987-93), happened in hip-hop hotbeds and active sites of the Jamaican diaspora, including London but especially New York and the wider Boston-Washington corridor. These recordings were published by hip-hop labels and largely circulated among hip-hop DJs; notably, they did not enjoy a particularly strong reception in Jamaica. Raggamuffin hip-hop is diaspora music par excellence, and hip-hop music par excellence too, we’d like to argue.

For further context, we’ll direct you to Wayne’s article for Cluster Mag, published simultaneously today with our mixtape. Here, we would like to focus more on the form and enterprise of making a mix in order to talk about musical and social history -- and to let other voices speak for themselves. We contend that focused, quasi-genealogical mixtapes like this one serve as importantly and insistently audible versions of the stories we tell together -- in other words, as musically-expressed ideas about music.

In this particular case, we take a subgenre as our subject, but the subject of a mixtape could be far more focused or diffuse. One could center on the life of a particular sample or melody, or a geographical subset of a subgenre (e.g. Pace’s “Beantown Ragamuffin”) or a slice or two of a city’s soundscape (as in Wayne’s Boston Mashacre and Smashacre) or a plethora of other angles into music culture and society. We’re thrilled to see IASPM embrace the format and delighted to offer a contribution.

While this mix is informed by ethnography (both our own -- see, e.g., Pacey's “Hip-Hop in the Hub” or Wayne’s “Bling-bling for Rastafari” -- and others’ -- e.g., Afropop Worldwide’s “Jamaica in New York City”), we propose that recordings like the ones in this mix comprise another, often overlooked part of the ethnographic record, a form of auto-ethnography. This musical auto-ethnograpy is especially important in genres like rap and reggae, which seek to document self and place and predicament, even while blurring lines between documentation and performance -- lines that are never clear in ethnography.

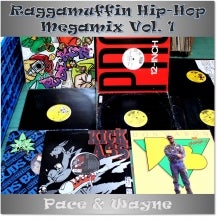

We produced the mix collaboratively, meeting on several occasions to conceptualize, listen through our respective collections, and winnow a tracklist. We decided to assemble three mini-sets each, covering different eras and areas. Later we combined them, in alternation, to make the mega-mix here. We live in the same city, but a lot of this work was facilitated by filesharing. The mix was recorded using vinyl as well as CD rips and mp3s. Some of the scratching you hear is courtesy of Pace, and some is on the records themselves. In addition to these moments where authorship blurs a bit, Wayne takes digital liberties with a number of tracks, producing edits that, for example, excise US-style rap verses in order to highlight patois excursions or choruses. Ethically speaking, all of these recordings circulated publicly via commercial and extra-commercial channels, and we believe these constitute a form of public culture, inviting a range of responses, including those enabled by cut-and-paste technologies.

Briefly, we begin by digging into the early days of raggamuffin hip-hop, when the sound of New York first became audibly infused by the sounds of Jamaica. (London, which also makes an important early appearance here, had long been suffused by reggae aesthetics.) By virtue of becoming hip-hop classics, some of these tracks bequeathed to the genre all manner of reggae references, among them the well-worn “zunguzung meme” (which inevitably rears its familiar head in our mix). As we move forward, we move outward, taking New Jersey, Boston, the Bay Area, and even Los Angeles into raggamuffin hip-hop’s remit.

We’ve chosen not to observe strict chronology or cut-off dates, but we do generally trace a thick, squiggly line from 1987 to 1993 -- the central, classic, and seminal period for the subgenre, in our opinion. We indulge some outliers from 1985 and 1994 (and later), to include a remarkable early example, a rare raggamuffin turn from Slick Rick, and a handful of notable Boston productions. Pace’s 3rd mini-set takes a special departure into another, related subgenre: dancehall party breaks, or records produced by DJs for DJs (many of them “white label releases with little identifying information) aimed at the memory banks of audiences accustomed to hearing hip-hop and reggae alongside one another in the mix. For all their influence, many of these recordings have grown obscure, but they deserve to do more than comment from the margins.

The cultural politics here emerges on its own, and on its own terms, but we want to call attention to the striking co-presence of gangsta and righteous themes throughout, especially a Jamaican-inflected Afrocentric militarism that broadly textured hip-hop’s pro-black turn in the late 1980s. The aesthetics of raggamuffin hip-hop combine sound and ideology rather explicitly at times. Even on remarkably raggamuffin sections of Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, one hears how a Jamaican accent seems inextricable from a certain hardcore radicalism. (And many listeners might be surprised how convincing and menacing Snoop’s Jafakin accent was back in 1992, decades before the Dogg recrowned himself a Lion.)

Our mixtape clocks in at exactly 94 minutes, which is convenient since ‘94 is the year we decided to “pull up” our survey (but maybe someday we'll “come again”). But the density of patois-peppered rap explodes in and after 1994, and simply closing out the decade, never mind touching the post-millennial wave of hip-hop and reggae interplay, would take us another hour and a half -- and beyond raggamuffin hip-hop per se, which names a particular moment. (Also, there are other good mixes that mine this territory: see, e.g., DJ Kikkoman’s “Kingston-Brooklyn Bridge” or El Canyonazo’s “Dubious Brethren.”)

If the whole point is to let these recordings speak for themselves, albeit edited and framed by two longtime close-listeners, surely we’ve offered enough commentary for now. Major props, shout-outs, and big-ups to all the artists and producers, DJs and audiences, record labels and others involved in producing the very musical, historical record we’ve tried to stitch together here. And thanks to all for listening.

Tracklist

Pace’s 1st mini-set:

Asher D and Daddy Freddy, "Ragamuffin Rub-A-Dub-Apella" (1987)

UTFO, "Pick up the Pace" (1985)

Asher D and Daddy Freddy, "Ragamuffin Hip-Hop" (1987)

Soul Dimension, "Trash and Ready" (1987)

Asher D, "Asher’s Revenge" (1988)

Asher D and Daddy Freddy, “Brutality" (1988)

Boogie Down Productions (BDP), "The Bridge Is Over" (1987)

Wayne’s 1st mini-set:

BDP, "The Bridge Is Over" (1987)

Shinehead, "Know How Fe Chant" (1988)

Just-Ice ft. KRS-One, "Moshitup" (1988)

JVC Force, "Puppy Love" (1988)

Masters of Ceremony, "Sexy" (1988)

Just-Ice, "Lyric Licking" (1988)

Masters of Ceremony, "Master Move" (1988)

Shinehead, "Gimme No Crack" (1988)

BDP, "The Bridge Is Over" (1987)

Pace’s 2nd mini-set:

BDP, "The Bridge Is Over" (1987)

Don Baron, "Young Gifted and Black" (1988)

Longsy D & Cut Master M.C. "Hip-Hop Reggae" (1987)

Sonya Alleye ft. Junior Rodigan, "Sorry Part 2" (1989)

Prento Kid, "Killer" (1997)

Motion w/ Ruffa "Gangsta" (1995)

Waynie Ranks, "Send Me" (1992?)

Wayne’s 2nd mini-set:

Poor Righteous Teachers, "I'm Comin Again" (1991)

Poor Righteous Teachers, "Easy Star" (1991)

Poor Righteous Teachers, "Shakiyla" (1991)

Fu-Schnickens, "Ring the Alarm" (1991)

Fu-Schnickens, "Generals" (1991)

Poor Righteous Teachers, "Strictly Mashion" (1991)

Fu-Schnickens, "Bebo" (1991)

Daddy Freddy, "Raggamuffin Soldier" (1992)

Pace’s 3rd mini-set:

Unknown, "Sound Bwoys Revenge" (199?)

Cutty Ranks, "Armed and Deadly" (1996)

Lady Saw, "No Long Talking" (1996)

DJ Excel, "Off the Hook" (199?)

Kenny Dope, "Axxis" (1992)

The Filler, "Rockin Mix" (199?)

Kenny Dope, "Supa" (1991)

Jamalski, "Let's Do It In The Dancehall (TNT Hip Hop Mix)" (1990)

Roxanne Shanté, “Dance To This (Dance To Cee's Zunga Zunga Mix)” (1992)

Jamalski, "A Piece Of Reality (Your Name Here Mix)" (1992)

Wayne’s 3rd mini-set:

Raw Fusion, "Hip Hip/Stylee Expression" (1991)

Dr. Dre, "Let Me Ride" (1992)

Dr. Dre, "Lil Ghetto Boy" (1992)

Dr. Dre, "The Day the Niggaz Took Over" (1992)

Daddy Freddy, "Jah Jah Gives Me Vibes" (1992)

Jamal-Ski, "Jah Jah Vibes" (1993)

Jamal-Ski, "Texas Rumpus" (1993)

Born Jamericans, "Instant Death Interlude" (1994)

Jamal-Ski, "African Border (Skeffington Mix)" (1993)

Slick Rick, "A Love That's True, Part 2" (1994)