Mad Planet

My Pulse nightclub was a small, dimly lit, underage nightclub called Mad Planet. Situated on the border of the hood and Milwaukee’s slowly gentrifying hipster bastion Riverwest, Mad Planet attracted a gloriously freakish assortment of shapes, sizes, orientations, and musical tastes. The dance floor was a magnet for goths, hippies and queens who came together every Thursday night to challenge the segregated landscape of the city through spirited dance competition.

Slithering onto the dance floor to the screeching sound of Marilyn Manson, the goths in their black-robed, white-powdered luminescence frowned in disgust as they performed their signature goth-style dance move––a backwards lean and slowly scooping, side-to-side movement. The more dedicated the goth, the further the lean without tumbling over. Leaping onto the dance floor to the melodious, soulful sounds of Lauryn Hill, the queens “strummed their pain” with someone nearby, locking lips during intermittent instrumental interludes. The more dedicated the queen, the more meticulous in her recitation of Hill’s lyrics and vocal riffs.

I entered Mad Planet’s schizophrenic dance floor to test the limits of my own working-class whiteness. Born out of wedlock to bicultural lesbian parents, I trespassed the boundaries of subcultural identification almost on a yearly basis. For a time, I slunk up to the club with black hair and nail polish. Then, after falling ill with mono (which, I determined, was brought about by an excess of negative thinking), I grew my hair out to my shoulders and began eating granola. I proclaimed my gender queer-dom, sporting rainbow necklaces, bright colors, and a couple of filthy dreadlocks.

Mad Planet was an incubator for social misfits who had internalized the stigmatization they faced outside of the nightclub walls on the basis of race, gender expression, and sexual codes of morality. The place permitted us to share our feelings of impotence with each other and, through the performative labor of our bodies, revise and reconfigure them ever so delicately into something undeniably strange and beautiful.

It has been said that failure sometimes offers creative and cooperative ways of being in the world, even as it forces us to face the dark side of life, love and libido (Halberstam 2011). For a shooter whose failure was one of belonging, violence emerges as the only expressive outlet for feelings of abjection. But his deliberately destructive actions at the Pulse nightclub if anything shows us how important it is to make room in our societies for failure—failure of heteronormativity, failure of phenotypical belonging, failure of cultural and behavioral prescription/adherence—so that we who fail society are found and recuperated by our kin on the dance floor.

There is beauty in failure.

Later, participating on the front lines of activism in India and the U.S. for nearly a decade, I have seen music and dance lift our queer and trans sisters and brothers out of feelings of abjection. While this violence upon queer liberation still hurts badly, it strengthens my resolve to find a way of embracing the failures of others on this mad planet and dance again.

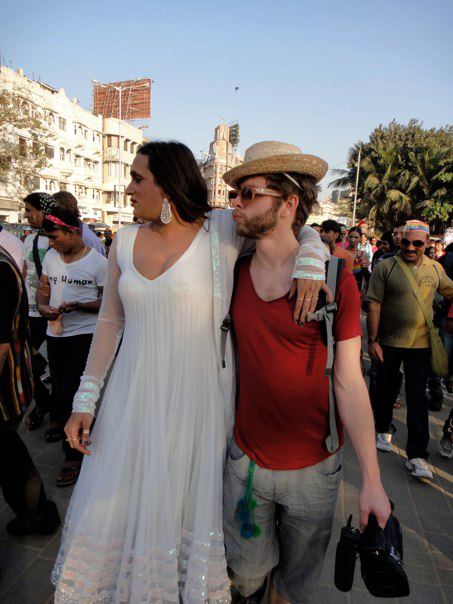

Photo of the author with Laxmi Narayan Tripathi at Mumbai's pride march, February 2, 2013; photo by Kareem Khubchandani

Photo of the author with the Dancing Queens in Mumbai; photo by Jeff Roy

References

Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Biography

Jeff Roy received his Ph.D. in 2015 from the Department of Ethnomusicology at UCLA. His doctoral research focuses on transgender and hijra performance through the lens of documentary filmmaking and arts activism, and has been supported by fellowships from Fulbright-Hays, Fulbright-mtvU, the American Institute for Indian Studies, and the Society for Asian Music. He is contributing a chapter in the upcoming volume Queering the Field: Sounding Out Ethnomusicology.