Made Out of Love: The Vision Festival Turns 20

The Vision Festival is an annual multi-arts festival centered around the avant-jazz aesthetic that has been developing in downtown Manhattan since the 1970s loft jazz scene. While largely a music festival, it always includes poetry, visual art, and dance. The festival takes place each June (or July) in New York City and draws artists and audiences from around the world. Each year, it is organized chiefly by dancer and choreographer Patricia Nicholson Parker.

The first Vision Festival took place in 1996. As Scott Currie described:

Taking what can only be described as an extraordinary and courageous leap of faith, [Nicholson Parker] guaranteed artists modest but significant fees for 31 performances of music, dance, and poetry over the course of five evenings (5 – 9 June 1996) at the Learning Alliance (324 Lafayette Street), with a program of six additional self-supported performances organized for the afternoon of Saturday 8 June. (2009:190)

Since its inception, the Festival has engendered a performing arts organization called Arts for Art, which, besides presenting the Festival, has presented a weekly concert series, several education programs, a seasonal concert series that brings its complex aesthetic into the Lower East Side’s numerous community gardens, as well as many other impromptu events.

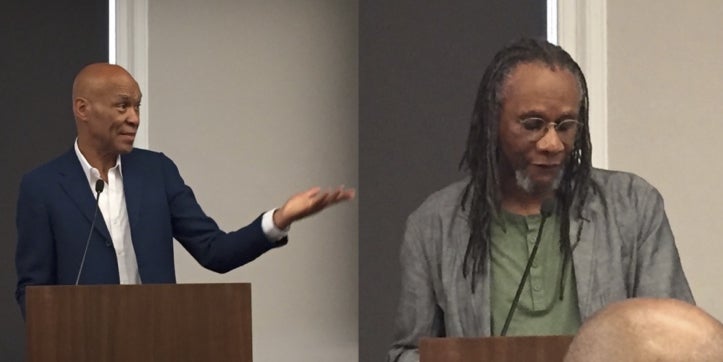

Earlier this month, the Vision Festival celebrated its 20th consecutive year. As part of the Festival’s anniversary celebration, an academic conference was held at (and co-Sponsored by) Columbia University on July 6. The day began with remarks by Michael Heller, who worked for Arts for Art years ago before going to complete a Ph.D. at Harvard, where he wrote his dissertation on the 1970s loft scene in downtown Manhattan (2012). Heller dedicated the conference to Amiri Baraka and Ornette Coleman, two giants whose absence has been keenly felt since they left the planet in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Heller introduced the first of four speakers, Scott Currie, who presented a paper that engaged jazz historiography. History and press coverage of the avant-garde, he argued, mirror post-modern orthodoxy in that they make the idea of artistic agency—the idea that music and art can change the world—seem absurd and impossible. Currie quoted Matthew Shipp, who would later appear on the panel: “Every aspect of society is geared toward making sure the ‘60s never happen again.”

Responding to questions, Currie weighed in on a terminological debate about whether the music should be called “free,” “avant-garde,” “jazz,” or anything (at all)/(else). In advocating the term “avant-garde,” he defined it as “attacking the institution of art with the intention of reconstituting the relationship between art and life.” For Currie “avant-garde” means art as revolution, though he observed that in common parlance the term has come to mean merely experimental. In his specific use of avant-garde—invoking political engagement—Currie declared that the Black avant-garde was the only true American avant-garde.

Bernard Gendron’s presentation sparked a heated response from the audience when he pointedly identified the specific moment when the “downtown scene” began. He cited George Lewis and Michael Dessen, whose formulation of Downtown I and Downtown II distinguished between, on the one hand, a “putative post-Cage” commonality among Philip Glass, Philip Corner, John Cage, et al. and, on the other, a group of people including John Zorn, vocalist Shelley Hirsch, et al. (Lewis 2008:331). Gendron posited a specific definition of a scene as a “geographically centered association of artists, institutions, and promoters on public display.” Based on this definition, he located the downtown scene as having originated at the Kitchen in 1972. Before 1972, he argued, there were post-Cageian artists working below 14th street, but no institutions and no visibility.

From the audience, Steve Dalachinsky, poet and devotee of Arts for Art and the downtown arts scene, rebutted this thesis. Dalachinsky argued that focusing on the Kitchen was too narrow and that there were so many other artists doing so much other work at that time and place, it was misleading to pinpoint the specific time and place of the Kitchen in 1972 as the beginning of the scene. Yuko Otomo, Patricia Nicholson Parker, and others concurred with Dalachinsky’s criticism. Brent Hayes Edwards invoked his role as moderator to mediate the two positions, insisting that we acknowledge the binary Downtown vs. Uptown as contested: Sam Rivers was working downtown but rehearsing in Harlem; did Black artists care about being Downtown? He reminded us of Fred Moten’s (2003) observation that people (ridiculously) talk as though the terms “Black” and “avant-garde” are mutually exclusive.

Ellen Waterman engaged agency and improvisation in terms of three “negotiated moments”: (1) corporeal archaeology, for which she gave an analysis of Gayl Jones’ 1975 novel Corregidora and discussed improvisation as a surreal strategy; (2) performativity, for which she discussed improvisation as a space to challenge and exceed the boundaries that society draws around subjectivities in view of Judith Butler’s argument that subjects are constructed by discourse; and (3) stance, for which she discussed listening, cognition, and perception.

Pianist and composer Vijay Iyer closed out the morning sessions, offering a critique of complacency and self-congratulation among jazz scholars and writers who extol jazz and improvisation for their power for social transformativity. He pointed out that, despite nearly a century of jazz, the United States is still a country characterized by deeply rooted social inequities, which have recently become more visibly documented in the form of cell phone videos of police brutality, and which have resulted in nationally televised mass protests like the ones in Ferguson in 2014 and Baltimore in 2015. Iyer discussed two of his own pieces through which he had meant to effect real change in political consciousness. One piece, Holding It Down: The Veterans’ Dreams Project, included poetry by veterans of color from the United States’ wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Iyer confronted audiences with the people who fought the wars that most of them would rather forget and with the oft forgotten fact that they were largely fought by people of color. The second piece Iyer discussed was a response to his feeling exoticized by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a predominantly white organization in a rapidly gentrifying Black urban area. Rather than tacitly accepting the institution’s attempt to use Iyer’s non-white visage as a mask to cover its glaring whiteness, he staged a die-in as part of his performance and drew attention to elitism in art. Iyer’s talk received a standing ovation.

After lunch, a panel discussion moderated by Michael Heller featured Patricia Nicholson Parker, her husband musician William Parker, musicians Joe McPhee and Matthew Shipp, former Arts for Art Board Chairman Brad Smith, and visual artist Jeff Schlanger. They raised ontological questions about freedom, discourse, and self-determination. One of the topics that Bernard Gendron had discussed was the journalistic response to downtown music. Precursors to the Vision Festival had not received any press coverage, and that fact was cited by Patricia and William Parker as one of the reasons for organizing the Vision Festival. William Parker said they were after the kind of attention that the AACM in Chicago and the Los Angeles musicians had been getting.

Several panelists emphasized the fact that the Vision Festival has always declined corporate sponsorship, relying instead on grants from foundations and government agencies and on private donations to fill the gap between its costs and the revenue generated from ticket sales and concessions. Matthew Shipp recalled how they had resisted appeals from George Wein to, in Shipp’s words, “be part of his plantation for a while.” The Vision Festival continues its tradition of community-based fundraising, both patronizing and accepting support from local (Lower East Side) businesses, and recruiting volunteers to staff events.

Another important issue raised was sustainability. The festival’s grass-roots beginning and its dependency on donations and volunteer labor would not necessarily predict 20 years of success in a demanding market like New York, its economic seismology having radically redrawn the socio-geographical map of the urban landscape upon which the festival was built. William Parker emphasized the importance of Patricia Nicholson Parker to the Festival’s longevity. He observed that there has to be someone dedicated to the administration and the fundraising, or it dies.

It is no secret that the survival of the Vision Festival has been due to Patricia’s extraordinary efforts. But after 20 years, Arts for Art has reached a crucial turning point. Todd Nicholson, former Associate Director, has returned from Japan to assume the position of Executive Director as Patricia moves from that position to Artistic Director. As a former Associate Director of Arts for Art myself, and having now worked with Todd, I can attest that there is certainly no one better suited to lead the organization into its third decade. However, I also know that with an organization that is built so much on personal relationships, volunteerism, and good will, a transition from Patricia’s personality to anyone new will be a tricky one.

The conference was capped off with a keynote address by poet Nathaniel Mackey, who was introduced eloquently by Robert O’Meally. Mackey spoke about poetry as a performance art. He elaborated on the meaning of the breath in poetry and in jazz, relating them and illustrating the multivariate (and poetic) use of the breath in jazz through vivid audio examples by John Tchicai and Ben Webster. And he spoke of the politicized breath in the past and in the present: the last words of Eric Garner, now a slogan for the Black Lives Matter movement, and the observation by Fanon, “We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe.”

Now, after all this serious talking, we had a big, gorgeous music and arts festival. It was a fitting commemoration of a milestone year. There had been already been an evening of films at Anthology Films on Second Avenue downtown: one film on Billy Bang, the other on William Parker and Hamid Drake. For six days after the conference (July 7–12), music, dance, poetry and visual art were presented at Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square South in Greenwich Village. The attributes of the space—an enormous marble room with 30-foot ceilings—presented acoustic challenges to the production team, led by one of the Vision Festival’s perennial unsung heroes, Bill Toles. Nevertheless, the performances were exceptional, even for a Vision Festival.

While my volunteer duties kept me out of the theatre for many of the performances, I witnessed several unforgettable performances. The first day of the festival featured musicians from the AACM, many in from Chicago and elsewhere, who were celebrating the 50th Anniversary of their own organization. On Wednesday night, the Sun Ra Arkestra got everyone on their feet while bringing the house down, and on Thursday, Milford Graves’ group, which included William Parker and Charles Gayle, displayed inestimable heights of sonic consciousness. I missed Ingrid Laubrock on Saturday night, but the community was abuzz after her set, as they were after Steve Dalachinsky’s poetry reading.

One of the most memorable performances for me was Larry Roland’s poetry; afterwards, he told me, “Everybody thinks I’m a bassist. I say, I’m a poet who has a bass.” Wadada Leo Smith and Aruan Ortiz took advantage of the room’s echo and delivered a profound lesson in space. William Parker premiered a breathtaking new composition—part of his Martin Luther King, Jr. project—with an ensemble that partnered familiar masters with exciting emerging artists. Pianist Connie Crothers was masterful in her collaboration with dancers Amanda Cray and Elaine Gutierrez. In fact, there was a marked emphasis on the non-musical art forms for this festival, especially with the inclusion of dance troupe Urban Bushwomen, whose aesthetic was unusual for the Vision Festival but who were very well-received. Visual art installations by Jo Wood-Brown, Jorgo Schäfer and Robert Janz, as well as visuals projected behind the stage by Bill Mazza, Jeff Schlanger and others, transformed the space into an immersive creative environment.

The production of the Vision Festival is a family affair, and for those of us who’ve been involved with it, every summer is a family reunion. We had food home-cooked by volunteers, masterminded by vocalist Anaïs Maviel, whose mother even flew in from Paris to help. The festival was unusually well staffed this year thanks to the meticulous efforts of William and Patricia’s daughter Miriam Parker, who also somehow gave a stunning dance performance in collaboration with her father on percussion and Michael Bisio on bass.

One person I spoke to during the festival was astute. Somewhat astonished he said, “Everybody just gives everything they have at the Vision Festival.” Sound is love; art is love; love is creation. The Vision Festival endures because it is made out of love.

References

Currie, A. Scott. 2009. "Sound Visions: An Ethnographic Study of Avant-Garde Jazz in New York City." Ph.D. Dissertation, New York University.

Heller, Michael C. 2012. "Reconstructing We: History, Memory and Politics in a Loft Jazz Archive." Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University.

Lewis, George E. 2008. A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moten, Fred. 2003. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Adam Zanolini is a reedist, writer, and ethnomusicologist based in Chicago, and a Ph.D. candidate in music at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Adam performs as part of the Participatory Music Coalition, the MB Collective, and the Border Bend Arts Collective in Chicago. He has also served as Associate Director of Arts for Art, presenter of the annual Vision Festival of avant-jazz in New York City. All of which are dedicated to an interdisciplinary/multi-arts approach to improvised creation. He is also part of the Live the Spirit Residency, presenter of the annual Englewood Jazz Festival in Chicago.