The Place of Race in Jazz Discourse: Storyville, Boston

Issues of space and place pervade jazz historical narratives, especially when considering conventional “up the river” histories. According to such accounts, jazz began in New Orleans (presumably a product of mixing influences in Congo Square and Storyville), traveled up the river to Chicago (to Lincoln Gardens or Austin High School), east to New York City (many cite the Cotton Club in the Swing era and Minton’s and 52nd Street for bebop), west to Los Angeles (and the supposed birth of West Coast Jazz on Central Avenue), and so on. Though scholars now debate the usefulness of such simplistic and often uncritical place-based narratives, they remain a stock feature of many jazz pedagogies.

Part of my work investigates how race and class impact the perception of particular places of jazz performance. In this blog post, I consider a specific site—George Wein’s Storyville: The Birthplace of Jazz, a Boston jazz club that opened in 1950 and lasted until 1960. Through close study of articles, oral history interviews, audio, images, and census information, I demonstrate how Storyville’s overt discourse of respectability—a discourse that privileged white audiences as “serious” connoisseurs of jazz art music—was rooted in race and class-based stereotypes.

Storyville, Boston

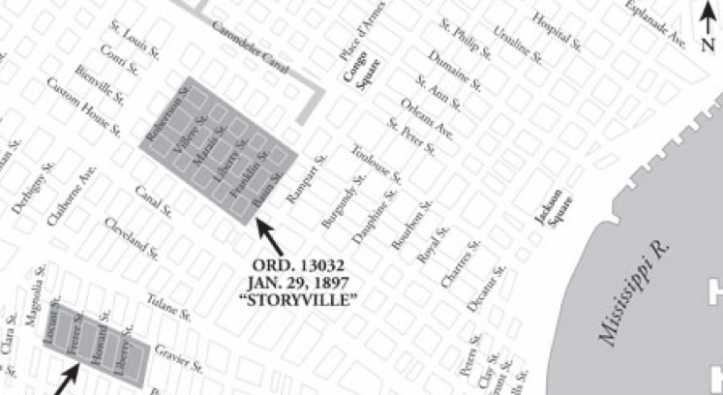

In 1950, Boston University graduate George Wein, the son of a physician, shocked his family by opening a jazz club in Boston’s Copley Square Hotel. Unashamed of what he described in his autobiography as “jazz’s seamy origins,” Wein took the name of his club from New Orleans’s former red-light district, Storyville, created by the New Orleans City Council at the turn of the twentieth century as a means to contain prostitution in the city. Storyville has long been associated with the beginnings of jazz: Cornetist Buddy Bolden, trumpeters Joe “King” Oliver and Louis Armstrong, and pianist Jelly Roll Morton grew up and played in and around Storyville. As Murray Forman argues, “it is in and through language that the values of place are produced.” Therefore, for Wein to take the name of Storyville for his club was to link his club to historical narratives of authentic jazz.

Postcard image of Basin Street, ca. 1908.

http://archive.oah.org/special-issues/katrina/Long.html

By the end of 1950 the Copley Square Storyville closed, due to a miscommunication with the management of the Copley Square Hotel. In 1951 Wein re-opened the club in the Hotel Buckminster, closer to both Boston University and Fenway Park. The Buckminster Storyville was not as successful as the Copley Storyville until Wein booked British jazz pianist George Shearing in September 1951. In 1953, Wein moved Storyville back to the Copley Square Hotel, which was under new management. The club stayed in the Copley Square Hotel until it closed permanently in 1960.

Location and Audience

In his recollections of Storyville, Wein does not specify which location he means (Hotel Buckminster or the Copley Square Hotel), suggesting that his concept of Storyville as a space remained largely unchanged, regardless of the actual place it occupied. Wein explained in a 2008 interview that Storyville’s audience was primarily white and college-educated:

Once we caught on, our audience was mostly made up of professors from the different local colleges. We didn’t draw many kids because they didn’t drink and most were under 21, the legal age limit then…The club attracted blacks when I had certain artists booked, but for the most part the audience was white and middle class.

Though Wein featured somewhat diverse groups of musicians including Dixieland Revivalists Bob Wilber and Jimmy McPartland and “modern” jazz artists such as Charlie Parker, the Modern Jazz Quartet, George Shearing, Sarah Vaughan, and Billie Holiday, many of these musicians were indeed successful among white audiences. Wein further explained that the club’s Copley Square location was ideal for the primarily white, affluent, and educated neighborhood surrounding it: “In terms of location, clientele, and the quality of the music, Storyville could be the first club poised to compete with the Savoy and the Hi Hat, both in an African American neighborhood.”

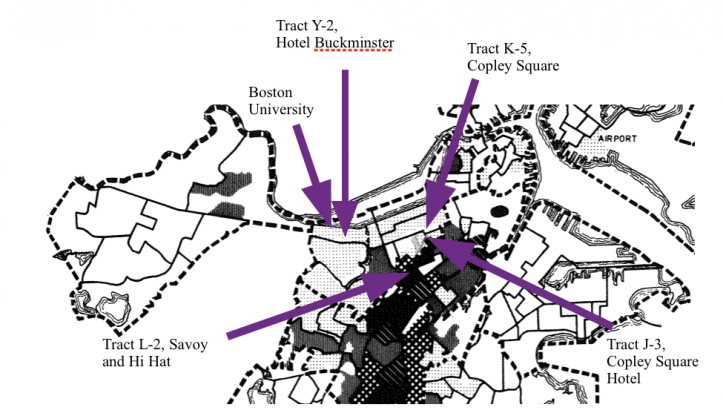

Census information corroborates Wein’s claims that the areas surrounding the Copley Square Hotel and Hotel Buckminster included a white, well-educated, white-collar audience. The image below shows a mapping of Boston’s 1950 census results regarding race and ethnicity, which indicates that while Copley Square was on the border of a distinctly white and a distinctly black neighborhood, the Copley Storyville itself was neatly tucked into a predominantly white neighborhood—and the Hotel Buckminster was located in an even more racially segregated neighborhood.

1950 Census map of Boston (the lighter the shading, the whiter the population, and vice versa). Includes Tract K-4A (Hotel Buckminster), Tract J-3 (Copley Square Hotel), Tract K-5 (Copley Square), Tract L-2 (Savoy and Hi Hat) and Boston University (for reference).

Source: Sweetser, Frank L. The Social Ecology of Metropolitan Boston: 1950. Boston University. Division of Mental Hygiene, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, 1961.

In the chart below, I compare the race, education, and type of employment across the Copley Square, Copley Square Hotel, Hotel Buckminster, and Savoy and Hi Hat neighborhoods. The confluence of race, class, and education in these neighborhoods is clear when comparing the Storyville neighborhoods with Tract L-2, the census tract that contained the Savoy and the Hi Hat jazz clubs. The Savoy and Hi Hat clubs were not only located in a majority African American neighborhood, as Wein noted, but the neighborhood also included significantly more blue collar workers, fewer professionals/managers, and fewer high school graduates. Ultimately, Tract L-2 demonstrates how place, race, class, and access to education intersected. In other words, perceptions of race inevitably rely on perceptions of class and education, as well.

Tracts | Race | High School Graduation | College Degree | Employment: Blue Collar Workers | Employment: Clerical / Service Workers | Employment: Professionals / Managers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

J-3 (Copley Square Hotel) | 1.8% | 52.2% | 9.7% | 32.9% | 45.3% | 21.8% |

K-5 (Copley Square) | 1.8% | 76.9% | 27.2% | 12.9% | 36.6% | 50.5% |

K-4A (Hotel Buckminster) | 1.5% | 77.8% | 24.6% | 17.7% | 34.7% | 47.6% |

L-2 (Savoy and Hi Hat) | 75.3% | 29.9% | 3.9% | 45% | 46.8% | 8.2% |

Census data for the Copley Square Hotel (Tract J-3), Copley Square (Tract K-5), the Hotel Buckminster (Tract K-4A), and the Savoy and the Hi Hat (Tract L-2).

Storyville as a Listening Room

Although Wein drew upon Storyville, New Orleans’s authenticity, he simultaneously distanced his own Storyville from the shady reputation of its namesake, insisting that “Storyville was a respectable place.” He stressed that his vision of Storyville was that of a “true music room. Storyville was never a joint. We had no floor show, no drug dealers or resident hookers. We kept things clean.” For Wein to call his own Storyville “respectable” and emphasize its freedom from drugs and sex work was another way of explicitly naming it a white place, a racial designation further underscored by associations with affluence and education, and in direct opposition to working class black places.

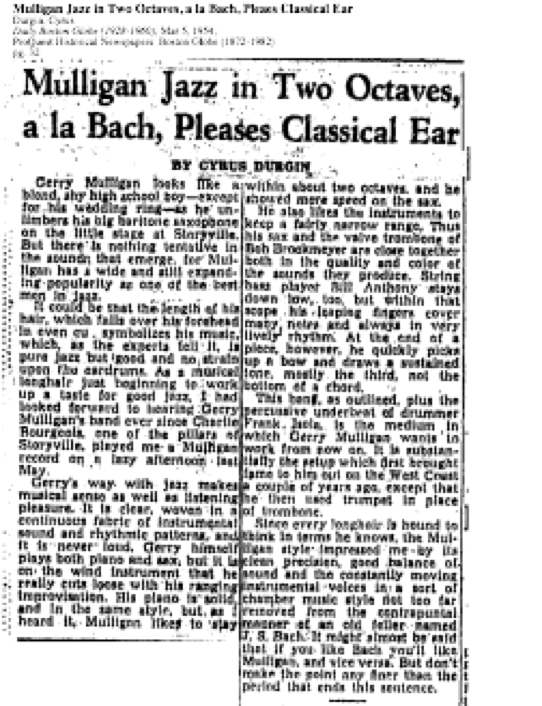

Unlike Storyville, New Orleans, George Wein’s Storyville was indeed known by its patrons and by music critics to be a “respectable” club. One way in which critics implied Storyville’s whiteness was by invoking the necessity for “serious” listening at Storyville. In 1953, Nat Hentoff referred to Storyville’s “relative silence.” Cyrus Durgin, a music reporter for the Daily Boston Globe, also wrote about Boston Storyville’s apparently surprising need for “attentive listening.” A self-described “longhair” (i.e. lover of European classical music), Durgin used Storyville as an example of how jazz had become a “serious” music, calling it Boston’s “best temple of jazz” in 1954. Durgin offered the actions of Storyville’s audiences as “proof” of jazz’s shift toward “attentive listening performances” by the Gerry Mulligan and Dave Brubeck Quartets—both heard as predominantly white groups by their audiences.

Some people do talk, but not many, and conversation is frowned upon. Most of the customers are there to listen, to Mulligan’s closely-woven musical strands that sound not unlike syncopated Bach, or to Brubeck’s resourceful piano style, with its moving voices of counterpoint and its fascinating shades of harmonic and instrumental color.

In this passage, Durgin not only described Storyville as a relatively quiet listening experience, in which any talking was limited to only brief interactions, but he also related the necessity for such close listening only to white musicians, through his descriptions of Mulligan and Brubeck’s Bach-like and contrapuntal music.

For all of George Wein, Nat Hentoff, and Cyrus Durgin’s insistence that Storyville was a “quiet” place for listening to jazz, albums and radio broadcasts recorded live at Storyville suggest that quiet was a relative term. Though Durgin specifically highlighted silent audiences for performances by Mulligan and Brubeck, these musicians’ live recordings feature audience noise particularly prominently. Mulligan’s December 1956 recording at Storyville offers a glimpse at the frustrations some jazz musicians felt even toward Storyville’s “quiet” audiences. Audience chatter is prevalent throughout the tracks, but perhaps the most striking moment is found during “Limelight,” when Mulligan has an infamous encounter with a whistling audience member.

While Mulligan’s outburst could have been unique, especially at a club so renowned for its “respectful” audience, the Storyville audience seems to have been noisier than Cyrus Durgin or George Wein cared to remember. For instance, on a Brubeck recording from October 22, 1952 at Storyville, a patron whistles along with saxophonist Paul Desmond on the melody of “You Go to My Head.” Rather than accost the patron as Mulligan did, the characteristically non-confrontational Desmond simply deviated enough from the melody to throw off the whistler, who eventually stopped.

Images of the Brubeck Quartet at Storyville complicate the dichotomy between “serious” and participatory listening. (See one image here; while this is the only archival image available online, other images in the Brubeck Collection show more of the Storyville scene.) Indeed, the audience pictured seems to demonstrate the kind of focused listening described by Durgin and Wein—all visible bodies are focused on the stage and the Brubeck Quartet, all bodies pictured seem still. But the tables and the items left casually on them remind us that Storyville was a social place—a nightclub—in which it was not only acceptable to drink and smoke, talk and laugh, but in which such behaviors were expected. Even if Brubeck’s music was, as critics often claimed, more “complex,” more “intellectual” for its references to European classical music, audiences could choose to focus their listening entirely on the Brubeck Quartet—or not.

The Copley Square Hotel Storyville today (at the Fleur-de-lis)—it’s now an exclusive club with images reminiscent of Storyville, New Orleans (http://storyvilleboston.com). The Hotel Buckminster Storyville is now a Pizzeria Uno.

Conclusion

By acknowledging Storyville as a “listening” club, Wein, Durgin, and other jazz writers implicitly linked the club and its audience members to whiteness—even if audio accounts suggest that the audience was less silent than suggested in written accounts. Put simply, Storyville remained a club, in which conversation and drinks were not merely accepted, but expected, and although musicians such as Mulligan insisted on being heard as “serious” artists, audiences nevertheless felt comfortable attempting such participation. In other words, Storyville was a place in which primarily white, educated, middle and upper-class audiences could be privileged as “serious” listeners by white jazz commentators—even if the behaviors and modes of listening they enacted were actually not “silent,” “quiet,” or “attentive.” Regardless of the actual experience of listening at Storyville, the club’s location in a white neighborhood, white audience, and overt discourse of respectability directly countered narratives of black places, such as Storyville, New Orleans, which remain rooted in race and class-based stereotypes—narratives that were distinct from places of whiteness.

The stakes of research on race, class, and place are not limited to historical reconstructions such as the case study I have investigated here, but rather are imperative to understanding the full spectrum of present-day race and class-based privileges and injustices. Living in St. Louis, in which every municipality that makes up the greater metropolitan area carries with it an implicit association with race and class, the importance of such research on the race of place is all too obvious. Consider, for instance, the infamous “Delmar Divide” and the policing of black bodies in implicitly white public spaces, including but not limited to the very visible deaths of Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Trayvon Martin. For two recent examples of such policing leading up to the Missouri primaries, see:

http://www.riverfronttimes.com/newsblog/2016/03/14/how-st-louis-stopped-donald-trump

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/kansas-city-pepper-spray-trump_us_56e51dc1e4b065e2e3d637f1

But it is not enough to simply identify places of blackness or of poverty (nor is it appropriate to assume that places of blackness are places of poverty, or vice versa). We need to also make places of whiteness and of affluence visible. In his explanation of the importance of race to space, political philosopher Charles Mills argues that normative space, or space that is seemingly not raced, is frequently raced white: “Space is just there, taken for granted, and the individual is tacitly posited as the white adult male, so that all individuals are obviously equal.” Likewise, George Lipsitz argues that public spaces not often discussed in terms of race are usually raced white, or privilege whiteness. I would add that in addition to privileging whiteness, such normative public spaces also privilege whiteness as it intersects with upper and upper-middle class identities, and educational backgrounds—and further, masculinity, heterosexuality, and ability. Such privileges are not completely invisible—as Sara Ahmed, bell hooks, and George Yancy argue, whiteness is largely not invisible to the people of color who experience the negative manifestations of white privilege daily. So in closing, I emphasize that it is only by making places of whiteness visible to white people that we can begin to alter, and indeed dismantle, the associations of whiteness, affluence, and educational status with discourses and spaces of respectability.

Notes

Cover photo: Storyville, ca. 1955. Detail of a photograph by Nissan Bichajian, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Libraries, Rotch Visual Collections. http://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/34173

References

Ahmed, Sara. “Declarations of Whiteness: The Non-Performativity of Anti-Racism.” Borderlands E-Journal 3, no. 2 (2004).

Durgin, Cyrus. “Jazz Moves to Newport as Serious Music Form.” Daily Boston Globe (20 June 1954), C79.

Frith, Simon. “Rhythm: Race, Sex, and the Body.” In Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music, 123-144. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

hooks, bell. “Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination.” In Displacing Whiteness: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, edited by Ruth Frankenberg, 165-179. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997.

Forman, Murray. The ‘Hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip-Hop. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2002.

Hentoff, Nat. “Counterpoint.” Down Beat (1 July 1953), 8.

Lipsitz, George. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2011.

Mills, Charles W. The Racial Contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Sweetser, Frank L. The Social Ecology of Metropolitan Boston: 1950. Boston University. Division of Mental Hygiene, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, 1961.

Wein, George. Myself Among Others, with Nate Chinen. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003.

Wein, George with Marc Meyers, “Interview: George Wein (Part 1)” Jazz Wax (23 July 2008): http://www.jazzwax.com/2008/07/interview-georg.html

Yancy, George. Look, A White!: Philosophical Essays on Whiteness. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2012.

Kelsey Klotz recently completed her PhD in Musicology, with a certificate in American Culture Studies, at Washington University in St. Louis. She is currently a Senior Teaching Fellow at Washington University, and has also been awarded the Graduate Student Fellowship from the Center for the Humanities and the Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching. Her dissertation, “Racial Ideologies in 1950s Cool Jazz,” examines the cultural construction of whiteness in histories of cool jazz.