“Dununa Rivesi” (“Kick Back”): Dancing for Zambia

Introduction

In 2016, the popular song “Dununa Rivesi” featured prominently during elections in Zambia. Newspapers and other print media published numerous articles about the song. Radio stations blasted the song on the airwaves, and kids and grown-ups, regardless of their political affiliation, danced and sang along to the song in a variety of spaces. The song was originally a political theme song for the governing Patriotic Front party, but in addition to being performed at Patriotic Front (hereafter PF) campaigns, “Dununa Rivesi” was also heard at parties and nightclubs.

A cover of the song, titled “Dununa Forward” and sponsored by the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND), was also released. Zambians in the United States, Poland and beyond performed and uploaded choreographed versions of the song to YouTube. No single song has had such massive appeal in the history of Zambian political music.

Drawing on fieldwork, interviews with popular musicians, music fans, political leaders, and literature on Zambian music and politics, this paper examines what led to “Dununa Rivesi” becoming one of the most popular songs in the history of Zambian popular music. I argue that nostalgia evoked by “Dununa Rivesi” is one of the main factors that propelled the song’s popularity, enabling politicians and PF supporters to mobilize publics during Zambia’s August 2016 elections.

“Dununa Rivesi”

“Dununa Rivesi”

The Patriotic Front party was founded by Michael Sata in 2001 after he expelled himself from the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) government. The PF’s women’s choir, founded exclusively in order to compose and perform campaign songs as a way to mobilize publics for the PF, composed “Dununa Rivesi.” The PF Entertainment Committee, which was entrusted with the duty of facilitating the production and circulation of a campaign song for the 2016 elections, paid for studio time at Shenky Sugar Sounds Studios now in Lusaka, and sub-contracted singers Jordan Katembula (one of Zambia’s most celebrated pop musicians, also known as JK), Kayombo, Felix, and Wile to produce a pop rendition of the song (Christopher Linenga, personal communication, 2017).

Figure 1: Jordan Katembula (JK) [Picture courtesy of Fortress]

The song “Dununa Rivesi” is an example of Zed Beats, one of Zambia's most popular music genres. Zed Beats (colloquial for “Zambia’s beats”) blends traditional Zambian music with R&B, reggae, rap, and hip-hop. The genre is primarily popular among lower-middle-class youth. However, the “Dununa Rivesi” Zed Beat transcended age, social class, national boundaries, and politics.

“Dununa Rivesi” is not the first political theme song to have taken over the soundscape during moments of political transformation in Zambia. For example, music was at the center of the struggle that led to the country's independence from Britain on 24 October 1964 (Sardanis 2003a:11). Njekwa Anamela, Vice President of the opposition United National Independence Party (UNIP), has also observed that Zambians used chachacha music as a rallying point to fight against colonialism (personal communication August 2017). In Africa: Another Side of the Coin: Northern Rhodesia’s Final Years and Zambia’s Nationhood, Andrew Sardanis (2003b:91) narrates the origins of Zambia’s chachacha:

A lot of property, including government offices and even schools, was damaged. The chachacha had started. The chachacha had since been immortalized as Zambia’s independence struggle. It took its name from the Congolese Afro-Cuban r[h]umba music song “Chachacha Independence” which in 1960 celebrated the end of Belgium rule in the Congo. In typical Zambian folk humor, it portrayed the people of Zambia dancing chachacha and “shaking the colonial government out of office.”

The Zambia's 1950s and 60s chachacha music was mostly sung acapella, although drumming and later Western instrumentation accompanied the singing.

However, the direct use of popular music in Zambian politics is a relatively new trend. The 1991 election, which transformed Zambia into a multi-party state, was the first time political parties used recorded popular music in their campaigns and jingles. UNIP, the ruling party at the time, produced an album on cassette that included the track “Keep the Flame Burning,” a song that UNIP supporters and sympathizers danced and sang along to. Since then, popular music has become an important part of political propaganda and campaigns.

For example, musician Wesley Chibambo's “Donchi Kubeba” (“Don’t Tell Them”) mobilized publics to vote for the PF, and arguably contributed to their success in the 2011 presidential election, when they displaced the MMD who had been in power for twenty years. However, “Dununa Revisi” represents something new in the Zambian political scene. It was the first time that a political campaign song became popular in multiple spaces among multiple publics. In "Politics and Counterpublics," Michael Warner (2002:50) defines a public as "a concrete audience, a crowd witnessing itself in visible space as with a theatrical public." I draw on Warner’s definition and use the word “public” to refer to collectives that share visible and/or virtual spaces, and “Zambian publics” to refer to such collectives that identify themselves as Zambian.

I contend that “Dununa Rivesi” changed the way people hear politics. As Zambian journalist Nkweto Mfula (2016) writes, “One thing is true, this election campaign will go down in history as one where musicians stole the show. JK et al’s ‘Dununa Reverse’ has been at the peak of the Patriotic Front campaigns.” In the following section, I will elaborate on some of the factors that led to the massive appeal of “Dununa Rivesi.”

Factors that Led to the Appeal of “Dununa Rivesi”

Use of familiar musical elements, famous Zambian musicians, and local dialects are some of the factors that enhanced the appeal of “Dununa Rivesi.” The song features Nyanja, Bemba, and Lala languages. Nyanja and Bemba are the main languages spoken in the urban regions where most of the electorate is concentrated. Lala is perceived as a phonetically humorous language by most Zambians, especially those in urban areas who associate the language with rural life. According to Milimo Muyanga, a Zambian reggae musician, "there is something about the intonation in the Lala language that makes it sound non-serious. Lala is liked by people because it is a bit funny sounding...even when he [singer Wile] is talking about a very serious thing...it still sounds as if he is joking" (personal communication, August 2017). English is the official language of communication in Zambia, and one would expect political songs to be sung in the Queen's language as was the case with UNIP's “Keep the Flame Burning.” However, the PF has always claimed that it is the party for the marginalized lower-middle class. Therefore, the use of local languages in the song can be understood as a deliberate effort to reach out to the lower strata of society that is mostly semi-illiterate and communicates primarily in local dialects (Bemba and Nyanja) as opposed to English. Zondani Banda, a Pittsburgh denizen who migrated from Zambia over fifteen years ago explains: “I don’t support the PF, but I liked the song because it was a good song and it was sung in a language I speak [Nyanja]. I don’t think the song would have had the same impact if it was sung in English" (personal communication, 20 April 2017). Although Banda is literate and does not live in Zambia anymore, he asserts that use of local languages made the song appeal to him.

The text of the song is comical and mostly makes fun of the opposition. For example, Wile’s rap in Lala:

“…under five politics nebo nshitite fyamusangowo”

(“I don’t do stuff like under-five politics”)

In Zambia, infants and children under the age of five are routinely immunized against polio and measles among other diseases. The mortality rate in under-fives is higher in comparison to the mortality rate in children older than five years (Ministry of Community Development Mother and Child Health 2015:10). Therefore, it is assumed that children five years and older have a stronger immunity against disease and their lives are not as fragile as the infants’ and under fives’. Wile here is implying that Lungu, the PF candidate, who is far stronger [politically] than the candidates in the opposition, is not in the same league as his weaker rivals.

The next few lines are specifically directed at Hakainde Hichilema, the opposition UPND presidential candidate, who had run for the four previous presidential elections before 2016, winning none, with “Dununa Rivesi” guaranteeing Hichilema’s fifth defeat:

“Webo chimo nomwana wandi Saulos webo wapona grade seven seventeen times per hour. Five times ulepona chabe? Chita retirement webo”

(“You are the same as my child Saulos who failed his grade seven exams seventeen times…Five times you have failed. You should retire [from politics]”)

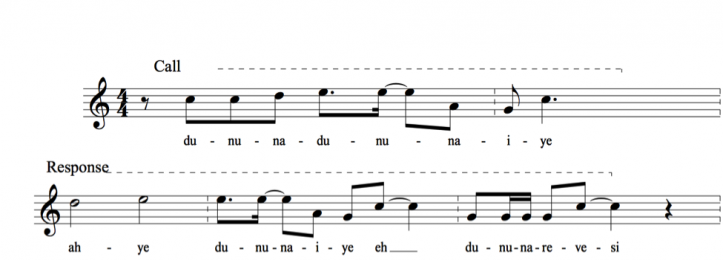

Rhythm also played a role in making “Dununa Rivesi” appeal to a broader audience. Most Zambians easily related to the familiar rhythm section of the song, a 4/4 generic drum pattern colloquially known as bustele among Zambian music fans. The bustele style which was popularized by musician Moses Chipimo, aka Mozegator, in the mid 2000s has its roots in sporting events, particularly soccer, where supporters sing at the events as a way of cheering for their teams. Bustele performances involve singing and dancing and participation is open to everyone in attendance. The bustele style sometimes makes use of recycled rhythmic patterns from previously released Afropop songs. Use of call and answer is a common feature in bustele and Zambian folk music. The transcription in Figure 2 shows the text and melody of the chorus in a call and answer style:

Figure 2: Call and answer in “Dununa Rivesi”

Call: Dununa, dununa iyee (Kick it, kick iyee)

Response: Ayee dununa iyee (Ayee kick it iyee)

Dununa rivesi (Kick it back; reverse)

The Zambian public, as Zondani Banda observes, was drawn to the song because they understood the lyrics and could easily sing along (personal communication, 2017). These elements were central to the song’s appeal.

Chidunu and Nostalgia

However, alongside these musical features, I argue that the main factor that enhanced the song’s appeal was the sense of nostalgia it evoked. “Dununa Rivesi” contains a reference to Chidunune, a variation of hide and seek, a game most Zambians played in their childhood. “Rivesi” is a local dialect pronunciation of the English word “reverse.” Dununa, the root of Chidunune, means to kick the chidunu [a container that is used to play the game] away from the seeker. To dununa-rivesi on the other hand suggests kicking the container back to the seeker. Although the lyrical content in “Dununa Rivesi” is not related to the Chidunune song sang when playing the game of Chidunune, the song relies on the space in which Chidunune was performed. In “Dununa Rivesi,” Zambian publics “were kicked back” into these spaces in which they could experience the good old days of Chidunune in their imagined realities. S.D. Chrostowska observes that when nostalgia is at play, “the past is re-imagined along with the past's uncertainty about the future...A past exerts a pull on us because it is an open door to (real and imagined) possibilities” (2010:55). During the 2016 elections, the Zambian public relived the past of Chidunune in re-imagined spaces. In reality the past could only be relived if the incumbent president Edgar Chagwa Lungu could be dununa-reversed (kicked back) to office. This promise of experiencing a moment in the past associated with chidunune, mediated by “Dununa Rivesi,” was enough to convince the Zambian electorate to re-elect the incumbent president Lungu back into office in the 2016 elections. Cliff Jere, another Pittsburgh resident, observed that “most people voted for Lungu not because of what he stood for but because of “Dununa Rivesi”” (personal communication, 2016).

Figure 3: President / PF member Edgar Chagwa Lungu

Conclusion

Musicians in Zambia played a significant role in mobilizing and influencing publics during the 2016 elections. To mobilize support amidst contestation, the PF drew on musical resources to popularize its agenda and mobilize its supporters. I argue that the nostalgia evoked by “Dununa Revesi” in the Zambian populace was one of the main factors that propelled the song to become a hit, motivating politicians, PF supporters and non-PF supporters to use the song to construct spaces in which to communicate their politics.

References

Chrostowska, S.D. 2010. “Consumed by Nostalgia?” SubStance 39(2): 52-70.

Electoral Commission of Zambia. 2016. https://www.elections.org.zm/elections_faq.php (accessed 13 April 2017).

Engel, Steven T. 2005. “Rousseau and Imagined Communities.” The Review of Politics 67(3): 515-537.

High Commission of the Republic of Zambia in India. 2015. http://www.zambiahighcomdelhi.org/news_detail.php?newsid=15 (accessed 15 April 2017).

Koloko, Leonard. 2012. Zambian Music Legends. Lusaka, Zambia: Lulu.com.

Mfula, Nkweto. 2016. “‘Dununa Reverse’ Captivates.” Zambia Daily Mail, 10/07/2016.

Ministry of Community Development Mother and Child Health. 2015. “Introduction of Inactivated Polio Vaccine in the Routine Immunisation Schedule in Zambia.” UNICEF, Lusaka, Zambia.

Olick, Jeffrey K. 1999. “Memory: The Two Cultures.” Sociological Theory, 17(3): 333-348.

Pistrick, Eckehard. 2015. Performing Nostalgia: Migration Culture and Creativity in South Albania. Surrey, England: Ashgate.

Sardanis, Andrew. 2003a. Zambia: The First 50 Years. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Sardanis, Andrew. 2003b. Africa: Another Side of the Coin: Northern Rhodesia Final Years and Zambia’s Nationhood. New York: I.B. Tauris.

Sedikides, Constantine, Tim Wildschut, Jamie Arndt, and Clay Routledge. 2008. “Nostalgia: Past, Present, and Future.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5): 304-307.

Sheffer, Gabriel. 2003. Diaspora Politics: At Home Abroad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skinner, Thomas Ryan. 2015. Bamako Sounds: The Afropolitan Ethics of Malian Music. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Tembo, Benedict. 2016. “About ‘Dununa Reverse,’ Power of Music in Politics.” Zambia Daily Mail, 10/08/2016.

Warner, Michael. 2002. “Publics and Counterpublics.” Public Culture, 14(1): 49-90.

Biography

Mathew Tembo is pursuing a PhD in ethnomusicology at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, US. His research interests focus on the impact of 1990s economic liberalization and changing technologies on Zambian popular music. He has directed two documentaries on Zambian music (“Sing Our Own Songs” [2007] and “Music of the Bwile People” [2015]), and also maintains an active performing career, touring and recording music all over the world.