The Unexpected Impacts of a North/South Pacific Rim Cultural Exchange

Making Connections

Before this past August, I hadn’t seen the extended Radford and Te`arama family for almost five years, when I’d driven my family up the Al-Can Highway to Homer, Alaska. Now, seventeen members of the group were coming north, to Homer and four nearby Alaska Native communities.[i] Among my duties at the Pratt Museum is the role of “cultural liaison” with numerous groups—not always an easy task considering the local geography.

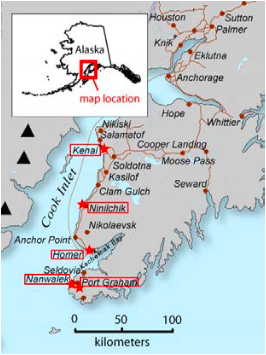

Kachemak Bay, which bisects the southwestern tip of the Kenai Peninsula, has been a crossroads of culture for thousands of years. The area North and encircling Cook Inlet is predominantly Dena’ina, a sedentary Athabaskan people closely related to the Native Americans of the Lower 48. The southern shore of Kachemak Bay, wrapping around to the Outer Coast on the Gulf of Alaska, is Alutiiq or Sugpiaq. These people formerly traveled by qayaq to various seasonal camps, but their travel, language, and customs were restricted by first Russian and then American colonization. The Russian influence remains particularly strong in Ninilchik, a mixing bowl with its own codified Russian dialect.

Nanwalek elder Nick Tanape, Sr. and my museum predecessor Gale Parsons developed a biennial Gathering event, Tamamta Katurlluta, bringing together regional Native communities with a guest cultural group in Homer. Representatives from each village land qayaqs on the Homer Spit, which are blessed by a Russian Orthodox priest, and all participate in a potluck, Native Youth Olympics games, storytelling, and a performance event showcasing each community.

Unfortunately, it’s not feasible to transport an entire village—much less five. For those on the South Shore of Kachemak Bay, roundtrip airfare to Homer is $160 (private boats are cheaper, but you can never count on the weather), another $250 to get to Anchorage. While those that have been able to participate in the Gathering events and spend time with a guest ensemble have raved about the experience, the opportunities for such exchange are extremely limited. Perhaps we should work to bring a cultural group into each village? I suggested such a tour to my contacts in each community, who were excited to work towards making it happen. Perhaps touring a performance group with whom I already had a relationship would make a good trial project?

I had known Te`arama for about ten years. When I had first made contact with Manu Radford in 2007, and asked if I might be able to play tō`ere with the group, he was more than welcoming. “There’s not too many Tahitians around Seattle. It’s too cold!” I ended up playing tō`ere and Tahitian banjo on-and-off with the group for about five years, until I migrated north. Now, I was looking forward to the reunion. Starting with their arrival in Anchorage on an overcast Sunday morning, I shepherded Te`arama on a whirlwind tour. Halfway on our drive to Homer, the sun finally peeked through clouds, reflecting on the rushing emerald waters of the Kenai River. “We’re gonna need another week,” reported Daniel from the backseat.

On the Road System

We stopped in Cooper Landing for a visit and tour of the Kenaitze Indian Tribe’s K’Beq Heritage Site. On Monday, the group offered ‘Ori Tahiti and tō`ere drumming workshops in Homer. Tuesday, a performance and workshops with the Kenaitze Jabila’ina dancers, as well as a program at the Ninilchik Traditional Council, after which the group was invited to work the Council’s set net. Nine fat silver salmon for the group, a gift that didn’t come without effort. The daytime temperature of around 60°F kept most of the group tightly bundled, particularly Nanave, who had only recently returned from weeks dancing in Tahiti.

The cultural exchange was an excellent opportunity for two cultures that are from very different parts of the world to get together to learn and discover not only their differences, but also their similarities. I heard comments like “that’s a lot like how we do it”.

-Michael Bernard, Kenaitze Youth Programs Director

There is nothing more gratifying than the sharing of traditions and practices with other native people who exercise similar cultural customs, and who can relate in every aspect to the indigenous way of life.

-Ivan Encelewski, NTC Executive Director

Across the Bay

Thursday morning, two small planes and one water taxi arrived in Nanwalek, at the western tip of Kachemak Bay’s southern shore. Off the road system and out of cell range, this village of about 250 people was a world away.

I was anxious at not knowing a lot of details of this visit. Although Gwen, the Village Council’s administrator, sounded excited in our planning conversations, my attempts to iron out an itinerary were met with vagaries. I was optimistic that with a positive outlook and faith, it would all work out.

Perusing glass cases in the small museum attached to the Council building, the visitors pored over stone net sinkers, stone lamps, Russian insignia, artifacts from the previous Orthodox church structure, and photographs of Maskalataq, a Sugpiaq/Russian Orthodox Christmas tradition. Sperry, Nancy, and Rhoda came to the door. This trio leads the local component of a Sugt’stun language program, through the regional Native organization, Chugachmiut. They spoke of their concern with language and culture, the nature of a “lost generation,” whose parents did not teach the language, and their work to educate the young ones. Community and identity. What matters most.

As introductions continued around the circle, the Te`arama dancers and musicians laid out their own stories. Over half of this traveling contingent are part of the extended Radford family, with direct Tahitian ancestry. The remainder bring diverse backgrounds to Te Fare O Tamatoa: Filipino, Guamanian, African American, and mixed ancestry. All have invested themselves into this practice of staying connected to, learning about, and perpetuating Tahitian culture. Many of the non-ethnically Tahitian performers have visited Tahiti with the group, and feel blessed to have the opportunity to be a part of this tradition. This eclectic and inclusive ensemble makeup can be seen throughout the Tahitian performance groups of Hawai`i and the Lower 48. The trio of Sugt’stun teachers listened, more than anything, and it was clear that the respective challenges of language and cultural preservation are one and the same. These two communities, urban Tahitian-Washingtonians, and autonomous Sugpiaq villagers, had more in common than they had in contrast.

Worldwide colonialization tried to eradicate native languages. In Tahiti, the language was preserved in Tahitian language Bibles and within English and Mormon protestant churches. In Nanwalek, there is a general pervasive sentiment, 'The hurt is still here'. Rhoda and I feel that same hurt.

-Manio Radford, Tahitian elder

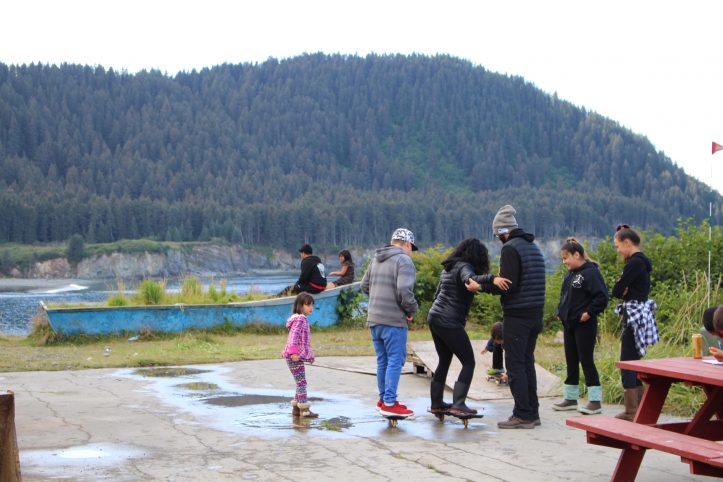

By the close of a potluck lunch, any barriers or anxiety between the host community and their new guests were complexly gone. Isaiah, Ryan and Reyna toyed on skate- and caster boards with a small gaggle of youth. The Te`arama directors and elders were making fast friends with their counterparts in the village. Solana sat at a picnic bench, entrusted with an 8-month old in camouflaged fleece bunting. “I’m not quite sure how I got this…”

The Council hall began to fill with, seemingly, the entire community. With Te`arama packed in one tight section of the bleacher-style seating, more than twenty local dancers filled the covered porch outside, ready to make their entrance. Sperry Ash, in bright aloha shirt, introduced the group and drummed them into the hall. The Nanwalek Seal Dancers relish individuality. Even in the group presentation of traditional drum dances, the assortment of costume, headdress, and facial decorations pale in comparison to every individual’s outgoing joy and enthusiasm. We noticed one dancer, Jacob, sporting board shorts with the unmistakable “Hinano Tahiti” logo.

After several pieces, Sperry returns to the microphone. “Now it’s time for a little rock and roll.” Joined by a backup band, the dancers launch into a series of pieces in the distinctly Nanwalek tradition developed by Joe Tanape. The bouncy, undistorted guitar melody drives the dancers as they imitate a series of local animals. The Seal Dance in particular showcases each individual in turn, impersonating a seal with puckered lips, lounging on the rocks, washing its face, and diving exuberantly into the sea.

The lengthy and energetic performance by the Seal Dancers inspired Te`arama to extend their set list. The audience was transfixed. Young children mimicked the motions of the aparima from their seats. The following workshops were packed. The enthusiasm and joy of the Seal Dancers carried through to their first attempts at ‘Ori Tahiti. The local villagers jumped in with carefree gusto, thrilled to join their new friends.

The community was in total bliss making us forget some of the daily disgruntles we may have with one another. There was an Elderly man I was watching as the group performed, he would not look directly as they danced, though his face showed happiness without smiling. Such beauty that touched my heart so deeply, I did not want it to end.

-Nancy Yeaton, Nanwalek

With more free time before the scheduled dinner and back in comfortable clothes, the suggestion was made to visit the lakes above the village. Isaiah and Ryan stayed in the village for a pickup basketball game with new friends, while the remainder of visitors rode on four-wheelers up the valley. The trail meanders, bounces, and splashes uphill, along the creek before crossing it at a shallow ford. “No wake, salmon spawning,” reads the sign. First stop: short walk through various berry bushes (ready for the tasting, but it’s a bum year for berries) to a scenic waterfall. Then on to First Lake, complete with rope swing (currently in use). At Second Lake lies “Wally’s World,” a group of cabins perfect for small or large groups to get away. Perhaps this would be a better stay? The guests were already planning their next visit.

We made it back to the village and council building as the potluck was being laid out. It was hard not to peruse the offerings as they arrived. After an Orthodox blessing, guests were invited to dig in. Seafood rice with periwinkles we’d seen women plucking from their shells earlier in the day. Seal heart and gravy over rice (delicious). Salmon five or more ways. A woman set a large bowl of mashed potatoes near the end of the food line. “You don’t want this! Fermented fish!” Then, “just try a little, tiny bit.” Teina smelled it, plopped a generous scoop on his plate. I sat across from him, with other Te`arama dancers. Sperry, at the next table, greedily scoops the fishy potatoes with smoked salmon strips. Teina doesn’t finish it, nor do I.

A young resident shyly walks around the table, giving origami flowers to the dancers, then returns to his collection of papers to craft more. There had already been formal gifts between the village council and the group, and gift bags for each performer. Another young dancer, who was front and center during the ‘ori Tahiti workshop, walks up behind Teina, gets his attention. “I want you to have this.” Teina was speechless. A hand-carved Alutiiq qayaq paddle. A symbol of his people. It’s a little rough around the edges, perhaps the product of a workshop. Nonetheless, the time, attention, and generations that went into this tool, and his willingness to give it, are staggering. In awe, Teina stands to hug this new friend. Once he goes, Teina clutches it, stares at it. Takes a while to digest the gift. This small village could simply not stop giving, thanking, welcoming.

A bevy of helpers transformed the room. John Kvasnikoff, First Chief, sat at the front of the hall, noodling on his electric guitar. Wally appears on bass, plus a drums, rhythm guitar and singer. The English Bay Band had been together, with some changes, since the mid-70s, occasionally gigging in Homer. As they played and the sun dropped deeper, dance party lights went up, and the floor was filled with all ages.

I cut out early from the music, which seemed likely to go all night long. It had to be midnight already. Out the back door of the council building, Daniel and I met Jacob and a few friends. Now cleaned up for the after party, he sported a smart Tahitian aloha shirt. “I don’t know where I picked this up, but it seemed appropriate!” He tried to lure us to the after-after party bonfire on the beach. I figured that, having introduced these distant communities, it was a good time for me to get out of the way. With many thanks, I was off to the school gymnasium and my sleeping bag.

Friday morning, it was clear that nobody wanted to say goodbye. Hugs lingered. Walking down the road among the visiting musicians, a four-wheeler came up behind us. One knee on the seat, Sperry slowed alongside. “Port Graham’s excited. Can’t wait to see you. It was all over Facebook.” His tone, bordering on stoic, always hinted at more. “But some of them here talkin’ about a kidnapping. Come an’ get you in the middle of the night, bring you back to Nanwalek.” Now he smiled, and sped off down the road.

Final Stops

In Port Graham, we learned that Te`arama’s visit prompted the dormant Paluwik Alutiiq Dancers to revive the ensemble, upgrading regalia and learning new songs. Pat Norman, First Chief, was thrilled to receive a written recipe for poisson cru, national dish of Tahiti, which Manio and Esther had made with locally caught halibut. Back in Homer on Saturday, Te`arama’s evening performance followed a program of contemporary solo and ensemble dances, and seemed to catch some of the audience off guard.

All of the kids in the community were thrilled to see something new and had a blast learning about their culture by being able to participate in the dance and play the instruments.

-Danielle Malchoff, Port Graham

Looking Back and Moving Forward

The members of Te`arama longed for more time, everywhere. How to balance such a tour with its expense, the need for downtime, and the availability of performers with day jobs? One dancer expressed regret from not having more prior knowledge and research about each of the communities they would be visiting. Another confessed to struggling with depression, but was amazed that walking alone on the Nanwalek beach, away from the village, was the most comfortably reassuring open-air experience in a long time. Good energy. And what happened around that bonfire in Nanwalek? Villagers and urbanite visitors talked about colonialism, gentrification, language and cultural preservation. Real conversation about real issues. There were more close conversations throughout the week than I could have captured—on shared experiences, traditional foodways, new challenges in the digital age, and more. Each community, wholly distinct, shared and co-created something very different with their guests. While some immediate impacts—personal and professional friendships, and the resurgence of the Paluwik Alutiiq Dancers—are obvious, others will only come out in the long-term. A subsequent cultural exchange tour, revised Tamamta Katurlluta Gathering, or as yet unknown collaborative projects may grow from these new relationships. This project has also allowed me, as cultural liaison, to further grow relationships with the nearby Native communities.

As for my own role as “culture broker” in this project, I had initial concerns about my bias in bringing a guest group with whom I had a personal connection. Was I pressing my own agenda upon these communities? My executive director and my wife had each assured me that wasn’t the case, but then a granting agency had asked about the community input and selection process…. At the end of the tour, however, I can say for certain that the benefits far outweigh potential conflicts, which never materialized. As the first such project for myself, connecting new friends with old friends was exciting and positive. Every community was thrilled about the impacts and results, yearning only for more time to share, meet, and learn from one another. When given a little extra time (say, 24 hours in a small village), the connections made initially through the sharing of music and dance run far, far deeper.

Pacific Islanders and Alaskan Natives definitely do share many similar values, practices and ways of life and it was awesome seeing those lifelong relationships being created and sustained.

--Solana Rollolazo, Te`arama dancer

On the drive to Anchorage, Gwen was headed the same way and met us all for lunch. There was already talk of another exchange, sending Nanwalek youth to Bellevue, or even Tahiti. Now, after the dust has settled, most all of the Te`arama performers remain connected to their new Alaska friends on Facebook. One Nanwalek dancer recently visitied the Radfords in Washington, and several Te`arama dancers have been invited and plan to visit Nanwalek for Orthodox Christmas and Maskalataq in January. As the overnight low at the end of November drops to 9°F, and it’s not yet winter, I hope they pack well. Regardless of the weather, it’s one outcome I never saw coming. The distant families will reunite once again.

[i] The Te`arama cultural exchange program was made possible by partnerships with the wider cultural, arts, and education communities, and in partnership with the Homer Council on the Arts. Funding was provided by the Rasmuson Foundation through a Harper Arts Touring Fund, administered by the Alaska State Council on the Arts. Additional sponsors include the Homer Foundation, Chugachmiut, Ninilchik Traditional Council, and Ninilchik Natives Association, Inc. In-kind partners include Kenaitze Indian Tribe, Nanwalek Village IRA, Port Graham Village Council, Port Graham Corporation, and the Center for Alaskan Coastal Studies.

Scott Bartlett has been Curator of Exhibits at the Pratt Museum in Homer, Alaska since 2012. He received an MA in Ethnomusicology and Graduate Certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa in 2011.