“Can I Get a Witness": Musicians Performing Politics in the U.S. Congress

“Can I Get A Witness”: Musicians Performing Politics in the U.S. Congress[1]

Introduction

To testify is to give a truthful account, to give personal evidence from one’s experience, and to give voice to one’s self. But the nature of truth is subjective and even a truthful testimony is a performance. As Anne Cubilié notes, testimony “exists in a performative relationship of language and action” (2005:3). In giving testimony, individuals give voice to their truth, and, in so doing, they present a particular version of their self, often in a very public, visible, performative setting. Such practices of testifying and truth telling have strong spiritual and music connotations, particularly, for instance, in the case of African American religious contexts, where the act of testifying is an integral element of gospel traditions (Boyer 1995; Ramsey 2003; Reed 2003). In addition to stating a personal truth, testimonies can articulate visions for society that manifest material effects or spur actions that can reshape social structures.[2] In many circumstances, the very act of testimony is imbued with political power. Witness testimony can impact legislation, cultural memory, and relationships between the state and oppressed groups—through, for instance, oral history projects that document genocides; or through reparative initiatives like Truth and Reconciliation commissions, as examined by scholars like Beverley Diamond (2012, 2016). In these cases, testimonies purportedly bring about reconciliation, they change minds, and they shape the laws and policies that govern our actions.

The act of testifying and truth-telling is also an act of self-fashioning or self-representation, in which a testifier’s words, manner of speaking, and self-presentation work to create an image of who they are. The power of such performances lies in their ability to seem as though they are unaffected—that is, not performed. In the US, popular musicians often engage in this kind of performance-as-non-performance through interviews, through public appearances, and, of course, through their music.

In this paper, we examine the performative nature and political influence of the testimonies by a particular sub-set of musicians in a very specific context: high-profile or celebrity musicians who participate in committee hearings in the United States Congress. In this particular setting, testimonies have the potential to have impacts both on politics and on public perceptions of musicians’ performances of self. Ultimately, we argue that by testifying, musicians can both influence politics and engage in a very public performance of self, one that contributes to audience acceptance of the credibility and authenticity of their musical performances. The purported truthfulness of testimony also raises ethical dimensions. We ask: if testifying entails giving voice to truth, whose truths do these testimonies give voice to, and whose do they silence? To explore this question, we first ask how musicians’ testimonies create meaning as performances of self that might shape how people hear music. Then, we ask how these performances both give voice and create silences—first, by considering how they position music vis-à-vis attitudes about the political process and U.S. exceptionalism; and second, by asking how musician testimonies relate to power dynamics within the U.S. popular music industry. We then theorize that musicians, by participating in the political process, shape public perceptions of who they are, what they represent, and how they should sound—a process that Timothy D. Taylor (2012) might connect to an individual’s brand-building, which Philip Auslander (2006) would consider part of creating a performance persona, and which Richard Dyer (2004 [1986]) would call a contribution to a “star text.” Finally, we evaluate the implications of our theory with empirical evidence.

The congressional committee hearings that we examine constitute the first step in the policy process. Each chamber of the United States Congress (the House of Representatives and the Senate) delegates the task of researching and writing legislation to a set of committees, a small group that controls policy development in a narrow domain (e.g. agriculture, armed services, natural resources, or transportation and infrastructure). Committees schedule hearings to explore the need for new legislation and, when necessary, identify and endorse potential solutions to a policy problem (Oleszek et al. 2016). To acquire the knowledge to move forward on an issue, committees invite a range of issue specialists—government officials, interest group representatives, academics, and celebrities—to speak at hearings. Musicians participate in hearings on a range of issues, from those that directly impact their livelihoods (e.g. intellectual property and copyright) to others of widespread public interest. Each witness delivers a prepared speech of approximately five minutes and then engages in a discussion with committee members. This dialogue creates a public record that defines the contours of policy debate as the committee proceeds to the bill-writing stage (Jones, Baumgartner, and Talbert 1993). By holding a hearing, a committee announces to the larger chamber, interest groups, the media, and the public that it is actively working on an issue.[3]

Who gets invited and why are these testimonies worth studying? Since witnesses exercise great influence in defining policy issues, committees carefully select individuals with expert knowledge, strong communication skills, and ties to Washington D.C.-based advocacy groups (Leyden 1995). This selection process brings to Congress musicians who have the approval of existing policy insiders, a demonstrated issue commitment (e.g., as a board member of an issue-related association or foundation), and enough star power to capture attention for the associated issue. Given this invitation process, musician testimony is an ideal subject for analysis. These testimonies are meticulous constructs that represent the culmination of an extensive effort to develop a reputation on an issue. Thus, they provide an excellent venue for studying how some of the most prominent individuals in the music industry use political advocacy to shape policy outcomes, their brand image and, in some cases, the image of the music industry as a whole.

Marsh, ‘t Hart, and Tindall (2010) have argued that studies of celebrity politics consist of an abundance of theoretical claims and anecdotes but are deficient in hard evidence. In response, scholars call for systematic and empirical research that “more precisely” estimates the “impact and importance” of celebrity political advocacy—in particular, studies that attend to the political consequences of and audience response to celebrity participation in the political process (Brockington and Henson 2015; Street 2012:347; Turner 2013). We rise to the challenge laid out by these authors by conducting an analysis of musician testimonies from the years 1995 to 2014.[4] To ensure that our judgments are not based on anomalous cases, we created a comprehensive list of all 83 musicians who have testified before Congress in this time period and our interpretive claims are premised on a reading of all these transcripts.[5] Further, rather than simply assuming that audiences “productively consume” celebrity advocacy (Turner 2013), we marshal statistical evidence to evaluate the extent to which audiences engage with these performances.

Major Topic (Subtopic) | Percent |

Health (Prevention, communicable diseases and health promotion; Infants and children; General) | 8 |

Labor and Employment (Employment Training and Workforce Development) | 3 |

Environment (Pollution and Conservation in Coastal & Other Navigable Waterways) | 3 |

Law, Crime, and Family Issues (Juvenile Crime and the Juvenile Justice System; Other) | 5 |

Social Welfare (Elderly Issues and Elderly Assistance Programs) | 3 |

Banking, Finance, and Domestic Commerce (Copyrights and Patents; Corporate Mergers, Antitrust Regulation, and Corporate Management Issues) | 49 |

Space, Science, Technology and Communications (Broadcast Industry Regulation; Computer Industry, Computer Security, and General Issues related to the Internet) | 14 |

International Affairs and Foreign Aid (U.S. Foreign Aid; Other Country/Region Specific Issues) | 8 |

Government Operations (General [includes budget requests and appropriations for multiple departments and agencies]) | 3 |

Public Lands and Water Management (Native American Affairs; General) | 5 |

Table 1: Policy Topics Discussed by Musicians in Congressional Committees, 1995-2014

Of course, musicians have participated in congressional hearings throughout the twentieth century and beyond, including those of historical significance like the HUAC hearings in the 1950s, hearings that established copyright legislation in the early twentieth century that continues to impact musical production today. For reasons of scope and length, we focus our discussion on musician testimonies from 1995 to present. According to Table 1, a majority of the musicians in our study testify both about issues related to musical performance, production, and consumption (the hearings classified as Banking, Finance, and Domestic Commerce or Space, Science, Technology and Communications), with the remainder addressing a broad range of issues of larger social concern. These testimonies are not “musical” performances per se (although, as we discuss later, some do involve music). But we argue that they are, whether implicitly or explicitly, performances about music. They are also part of what scholars of stardom and celebrity, after Richard Dyer (2004 [1986]), might call a performer’s “star text”: the representations, images, and depictions of a celebrity that create the popular narrative around that star and that continually produce meanings about and reflect understandings of her. In a similar vein, Philip Auslander (2006) has called on music scholars to understand musical performances as not only performances of musical works, but as performances of identity; not as self-expression, but rather, self-presentation. Musicians, he says, are not like actors playing characters: they appear as themselves. But they do behave in ways that carefully construct and present a certain version of themselves; a particular public persona.

We understand musician testimonies as actions, and the performers in question as active agents who are engaged in long-term performances of identity in the public eye. To use the term “star text” is not to imply that these performances are static texts. Instead, they are always actively being created and engaged, both by stars, who, in interviews, concerts, recordings, and, yes, congressional testimonies, are constantly elaborating on the narratives about them that circulate, and by of the viewing/listening public, who interpret, internalize, critique, and form impressions about such narratives, deriving meaning from them and using them as a basis for identifying (or not) with the artists in question. Stuart Hall’s (1980) work on reception, and the way that individuals not only decode messages in popular culture, but also actively negotiate their position vis-à-vis those messages (accepting some, rejecting some, and creating their own) is also a useful framework for understanding how stars’ cumulative performances and audience reception create meaning.[6]

The act of self-presentation that musicians (and, indeed, all celebrities) enact is part of the process of branding, which, as Timothy D. Taylor writes, is a means by which artists can position themselves as possessing a form of authenticity. Once an artist establishes a brand identity, they are held to “the expectations listeners have to a brand image of a music or sound or place or ethnicity” (2014:171). The context of the testimonial heightens the relationship between branding/self-presentation/star text formation and truth. The success of a branding effort depends on an artist’s ability to meet particular expectations of authenticity, and when that branding occurs via what is declared to be a testimonial, it underscores the purported truthfulness of the performance at hand.[7] As we discuss below, the very sounds of musicians’ voices in the committee chambers adds an additional element to this equation.

When musicians testify in government hearings, they are presenting themselves, constructing elements of their star texts, and performing truthfulness—and in so doing, they are shaping the way the public hears their music. As part of musicians’ star texts, these testimonies can bolster the established image of the musician in question. Jewel’s testimony on at-risk youth, for instance, lends authenticity to her performances as a singer-songwriter: many of her songs are about her experiences of hardship—her status in the singer-songwriter genre demands that she appear honest and truthful, and her heartfelt, personal account gives credence to that persona (U.S. House Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support 2007). Other testimonies, including those by Bono, Elton John, and others, also work as publicity opportunities, that market artists to philanthropic-minded audiences by using activist rhetoric (U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Foreign Operations 2004; U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions 2002).[8] In some cases, when widely known performers raise the profile of marginalized issues, these testimonies can have positive impact.

In addition to serving as a venue for artists to perform identity, these testimonies articulate attitudes about music that are not only coherent with artists’ personae, but also often support efforts by major record labels and organizations like the Recording Industry Association of America to regulate how music is made and sold. In music-related testimonies, the way artists describe music can influence legislation related to the music industry, and, as such, impact the lives and work of working musicians. And even when artists are not speaking on a specifically music-related issue, music often comes up over the course of their testimonies, often playing a key rhetorical role. In particular, we find that in many testimonies music is tied to values and ideas that are construed as being distinctly “American”: values such as hard work, thrift, and freedom of expression. Music is variously described in these testimonies as an art form, a form of self-expression, as an industry peopled by hard-working Americans, and as an emblem of U.S. exceptionalism. This kind of rhetoric, as we will see, often anticipates and forecloses debate. In hearings about music and intellectual property law, for example, it is used by speakers on both sides of the conflict between artists’ and corporate interests. A paradox thus emerges where artists speaking on behalf of large corporations use the rhetoric of self-expression in ways that may, in fact, inhibit the freedom of expression of less powerful artists. Whose voices, then, do these testimonies amplify? And how broad is their impact?

Musicians’ testimonies: Performances of self that shape listening

In some cases, artists use their testimonies to advocate for marginalized people, and, in so doing, consciously adopt marginal positions themselves. This gesture supports larger performances of authenticity that occur through their musical performances, and, as such, their testimonies have at least two purposes: to advocate for the marginal group that the artist is representing, and to advocate for themselves by demonstrating that they have an honest claim to the narratives and persona that they communicate through their musical work. Furthermore, these kinds of testimonies give credence and credibility to the very sound of performers’ voices.

Music scholars including Laurie Stras (2006), Simon Frith (1981; 1998), Richard Middleton (2000) and others, have demonstrated that genres like folk, punk, grunge, etc. place a premium on honesty and truth. As Frith (1981) argues, the ideology behind the singer-songwriter style of folk music that grew out of the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s is that it represents an “authentic,” and consequently valuable musical rendering of an individual’s experience. Stras shows that this ideology is manifest through singers’ vocal sound. In her work on voices that sound “damaged,” she writes:

Hearing damage in a voice connects the listener inescapably with the body of the performer, and the emotion in the performance is communicated as a testimony of personal experience rather than as an expression or invocation of the idea of emotion. The singer is no longer just a conduit for the composer’s musical intentions and the poet’s literary ones, but a person whose flesh speaks its history wordlessly through the voice itself. (2006:176)

Often, audiences assume that both the sounds and timbres of voices, as well as the thematic content of songs, reflect the true experiences and emotions of a performer. And while this is sometimes the case, performers also cultivate this kind of honesty, both knowingly and unconsciously. As Nina Eidsheim argues, the sounds of singers’ voices are the products of action: small, internal bodily movements that she calls “inner choreographies” (2009)—and these inner choreographies are shaped by the way that performers consciously or unconsciously learn how to sing, and by how they want their voices to sound to their listening public. If particular vocal sounds are performance postures that communicate history, experience, and truth, then the voices of artists who testify in congressional chambers support and provide context to the literal sounds of their singing voices.

Several examples illustrate just how this dynamic can play out. Art Alexakis of pop-punk-grunge group Everclear, which had a series of successful albums in the late 1990s and early 2000s, testified at a hearing on divorce and child support. At Everclear’s peak, their fans were drawn to the group because their grunge-inspired guitar licks and confessional lyrics about being disaffected kids seemed honest and truthful. One reviewer, for instance, called lead singer Art Alexakis the “poet laureate of divorced-dad rock,” and wrote, “what makes Everclear’s Art Alexakis so compelling right now is his ability to articulate that particular strain of anguish. As someone who went through it as a kid and has a daughter he’s putting through it right now, Alexakis is able to convey the pain of broken-home childhoods from two angles” (Herrington 2001:43). Alexakis was a truth teller, someone with the authority to speak about growing up in a broken home, not merely because he had lived it, but because he sounded like he lived it: he could articulate that “strain of anguish.” When Alexakis spoke before Congress, he described how writing a song about his absentee father led to connections with other people who had similar experiences:

This experience, along with the experience of having a child . . . affected me so much that I wrote a song about it. It is called “Father of Mine,” and it talks about, among other things, how my dad would send me a birthday card with a $5 bill, but that was the only time I heard from him growing up, basically. He didn’t understand, or he said he didn’t understand, how he was hurting me by not supporting me. There is a line in the song that says “My daddy gave me a name, and then he walked away.” . . . Apparently my song touched so many others, mostly kids, who were abandoned like me and could relate to my song, that my song did very well. (U.S. House Subcommittee on Human Resources 2000)

Alexakis’s emotional account of his experience growing up without a father, coupled with his reputation as a musical teller of truths, serves the interests of the politicians responsible for the hearing who need Alexakis’s compelling narrative to capture the interest of their fellow legislators, the media, and the public. It also serves as a public affirmation of the autobiographical nature of his songwriting and the truthfulness of his voice. In performances of “Father of Mine,” the song in question, Alexakis sings using timbre and gestures that sound petulant, emotive, and raw, conveying the impression that this is an unmediated emotional expression. Furthermore, the song’s lyrics frequently address the absent father figure, using deliberately childish language—Alexakis sings to “daddy”—which makes the song seem all the more genuine. Alexakis’s voice in the senate chamber affirms perceptions of the honesty of his voice on record.

A similar dynamic emerges in other testimonies by artists whose performances hinge on their purported authenticity. Singer-songwriter Jewel Kilcher, for instance, gave testimony about underserved and homeless youth that has a similar function to Alexakis’s: her established tendency towards autobiographical songwriting (often drawing on her experience of homelessness) gives the legislative proceedings an extra aura of honesty, while her emotive testimony bolsters her confessional performing persona. “I just slept in my car for a day, and it ended up lasting about a year,” Jewel testified. “I was singing in a coffee shop. I wrote music just to help myself feel better, and it seemed to make other people feel better, and they started coming to my shows” (U.S. House Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support 2007).

These kinds of performances extend beyond the words that musicians speak, also including the ways in which they present themselves in hearings and the messages that the very sounds of their voices convey. In some cases the sound of a performer’s voice gives credence to both their musical performances and to the subject of their testimony. When Cyndi Lauper testified at a hearing about providing resources to homeless LGBT youth, her accent and manner of speaking distinguished her from many of the other people in the room. Her pronounced Queens accent and use of colloquialisms made her statement seem unrehearsed and played on assumptions that regional, working class accents communicate a kind of populist authenticity.[9] Furthermore, Lauper’s voice makes it seem as though the working class have a voice in Congress, thereby legitimizing and authenticating Congressional proceedings by making them appear to be a site where seemingly “ordinary” Americans are heard. This particular type of performance of a street-wise identity is certainly not a tactic used only by musicians (Darr and Strine 2009). But in Lauper’s case, it recalls the squeaky, Betty Boop-like voice that she often uses when she sings, and it cements her status as a musical icon who is part of the community alongside her fans.

This kind of performance of authenticity and self can serve highly political ends. For instance, Hawaiian singer Don Ho, marketed as a supposedly authentic representative of Hawaiian culture to mainstream white audiences, testified at a hearing regarding a bill affirming Native Hawaiians’ right to self-determination. Ho advocated a fairly conservative position, claiming support for Native Hawaiian rights, but also calling for patience and caution in any pursuit of sovereignty. In his statement, Ho used language that makes him seem like a whimsical purveyor of Hawaiian folk wisdom. He refers to traditional Hawaiian foods, and he seems to speak in aphorisms.

You must pick the right time for sovereignty. You must take one step at a time to achieve your goal. Now, if you eat poi you eat poi one thing at a time, one scoop at a time, you cannot swallow all of the poi at one time. Now is not the time. The time now is to make that first step on a stepladder to get your sovereignty, but you cannot get over the jump all at one time, swallow all of the poi at one time you will get choked to death. (Native Hawaiian Federal Recognition 2001)

Ho’s history, as one of the few native Hawaiians that many white Americans would have seen represented in the media, gives his testimony a problematic air of authenticity that makes Ho seem like a legitimate spokesperson for Native Hawaiian interests, while perhaps overshadowing the voices of native Hawaiian activists.

This example raises an important issue regarding this kind of celebrity testimony: does it serve marginalized groups, or does it make their voices subservient to a louder, celebrity voice? This question is especially prescient when musician’s testimonies also appear to be part of an attempt to market themselves, by making audiences feel good about supporting them, which some have argued is a particularly cynical marketing move—it plays on people’s desire to do good by making them feel good about making consumer choices that they were probably going to make anyway (Littler 2009). When artists like Elton John testify about AIDS, or when Bono testifies about development in Africa, these efforts support other goals including bolstering the musician’s public image and selling products, records, and concert tickets. Even in cases where testimony is less explicitly a marketing ploy, the effects can be quite similar. Through their testimony, Jewel, Art Alexakis, and Cyndi Lauper helped establish their claim to communicate the narratives and persona in their music, which, in turn, enhances their ability to sell their music. As Brockington (2015) has shown, celebrity is a commodity that sells products when a celebrity is perceived as a credible spokesperson for a particular product.

American exceptionalism in musicians’ testimonies

In addition to taking advantage of consumer desire to do good, musician testimonies also affirm the positivity of the political process in the United States. Most of the artists who give statements speak of the privilege of appearing before government. For instance, LL Cool J opened his statement with “First of all, let me say that I am very honored to be here. It is a very special moment in my life” (U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Investigations 2003). Don Henley both described being honored to speak on behalf of songwriters, and thanked the committee for the opportunity to participate (U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation 2003). Such statements enforce the value of the democratic process; the artists are framing their involvement in political processes as exercises in civic engagement and an exemplification of the freedom and voice that U.S. citizens supposedly enjoy. The paradox here is that many are speaking on issues that illuminate the lack of voice and civil liberties that many in the United States experience. Even artists who are not U.S. citizens employ this rhetoric. For instance, in his testimony Bono (who is Irish) said:

You know what is amazing? Everywhere I go, people feel more American when you talk about these issues that affect people whom they have never met and who live far away. They feel more American. It is kind of extraordinary to me as an Irishman to observe this. I think that they are thinking big, as you always have. Sixty years ago there was another continent in trouble, my continent Europe in ruins after the Second World War. America liberated Europe, but not just liberated Europe; it rebuilt Europe. This was extraordinary. And it was not just out of the goodness of your heart, which it certainly was. It was very smart and strategic, because the money spent in the Marshall Plan was indeed wise money. It was a bulwark against Sovietism in the cold war. It was 1 percent of GDP over 4 years, I believe. I would argue that this stuff we are discussing today is a bulwark against the extremism of our age in the hot war. I believe there is an analogy. I believe brand USA, because all countries are brands in a certain sense, never shone brighter than after the Second World War, when a lot of people in my country and around the world just wanted to be American—wanted to wear your jeans, wanted to listen to your stereos, wanted to watch your movies. That was because this is an astonishing place, America. (Foreign Operations 2004)

Bono frames the United States as a benevolent force of good in the world, a harbinger of cultural and political freedom—and uses that rhetoric to compel U.S. politicians to intervene and combat poverty beyond its borders. In fact, Busby (2007) finds that Bono successfully won support for developing country debt relief and foreign aid to combat AIDS, from initially hostile Members of Congress, because he framed his arguments in terms of American moral values. In these cases, Bono’s moral appeals played a pivotal role in shaping U.S. foreign policy.

Similarly, in advocating for aid to New Orleans post-Katrina, Wynton Marsalis demanded that New Orleans’s musical history and culture be understood as American history and culture, and that New Orleans’s musicians be recognized for the work they have done as Americans:

There is a point I like to make about Louis Armstrong. We know he traveled around the world representing the United States of America. And we know, of course, of his genius as a musician. However, as a Nation, we have yet to embrace the actual fact of his artistry and what he represented to the world in the way that we perhaps should have done. We have not received the benefits that come with recognizing such a great figure. (U.S. House Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings and Emergency Management 2005)

Marsalis goes on to describe the kind of grassroots, populist culture that is often evoked in mythical depictions of the United States:

There are two types of people in the culture business. One is the culture from above. That is big organizations that you give money to. They might never meet the regular people. Then there is the culture from below. What makes New Orleans such a unique city in the world is that our culture comes from the street up. We have a combination of that elegance and wildness that is desired all over the world. (ibid.)

While both Bono and Marsalis are advocating for good causes, the rhetoric that they use in evoking notions of American-ness draws on a series of universalist tropes that inspire and appeal to emotional responses in a way that forecloses debate.[10] In Marsalis’s case, his description of New Orleans culture as American culture evokes a populist universalism and preempts racist and classist rebuttals to his call for reconstruction.[11] As Laver (2014) argues, Marsalis (particularly through his work with the Doha outpost of Jazz at Lincoln Center) is part of a genealogy of jazz musicians (including Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, and Duke Ellington) who have represented “American” values abroad. Such efforts, Laver demonstrates, emphasize freedom of choice—specifically, consumer choice under neoliberal capitalism—as part of America’s brand identity. A similar rhetorical thread emerges in committee hearings about music.

Constructing music-making as an “American” value

The question of whose voices are really being heard in musicians’ testimonies is particularly fraught in situations where musicians testify on issues related to music-making and the music industry. These testimonies illuminate conflicts between large record labels and smaller, independent companies and artists. Strikingly, however, players on both sides of this conflict use very similar rhetoric. They frame music-making as part of a system of values construed as exceptionally and distinctly “American.” Music, they argue, is a vital form of self-expression and a manifestation of freedom of expression. Working musicians, many argue, are hardworking citizens pursuing the American dream. They talk about music in ways that support nationalist myths of freedom and democracy, and frame music as an expressive practice that defines the national culture and identity.

Rhetoric about music as a distinctly American cultural product is particularly strong in hearings on issues related to music and intellectual property. In her work on intellectual property law, Joanna Demers (2006) outlines the ways in which copyright law battles emphasize the premise that copyright is a moral right—that protecting copyright is protecting justice and individual freedom. Demers demonstrates that in reality, copyright battles are more frequently disputes over ownership and the ontology of musical works, with financial remuneration often a primary concern. Cases such as Newton v. Diamond (2003), in which James Newton disputed the Beastie Boys’ right to use a legally-licensed sample of his recording of his original composition, Choir, reveal that the question of copyright and ownership raises issues about what constitutes a copyrightable musical work, both in the eyes of the law and in the context of musical practice, and raise questions about intellectual property law’s capacity to account for non-notated elements of performances (Toynbee 2013). While money was less of a motivating factor in Newton v. Diamond, other recent high-profile copyright disputes are more explicitly financial in nature. The court battle between the Marvin Gaye estate and Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke over alleged plagiarism in “Blurred Lines” shows how notions of individual creativity, justice, and fairness are deployed to justify claims to financial restitution. By appealing to a seemingly universalist ethos of fairness, the arguments in these cases foreclose debate. By further couching their arguments in nationalistic sentiment, the notion of control over copyright as a moral right emerges as a distinctly American value.

Nancy Sinatra testified at a hearing on the Performance Rights Act, and spoke against the radio broadcast exemption from royalty payments. Her statement frames intellectual property law as a moral issue and an issue of labor justice. She says:

For some of the singers and musicians that I know, especially back in the band era, their only compensation was their initial salary as a band singer, a stipend perhaps. But if they were to receive a royalty from their classic recordings that are still being played four and five decades later, it would mean the difference between having food and prescription drugs or not. (U.S. House Subcommittee on the Courts, the Internet, and Intellectual Property 2008)

Of course, this statement is somewhat misleading, as few of the musicians she describes would own the rights to the recordings in question, and would not receive a royalty even if broadcasters were required to pay one. But they function as an idealized and rhetorically powerful representation of music industry workers: Sinatra depicts them as hard-working and in search of a livelihood or a dream. This appeals to a sense of justice, but also masks the reality that the real beneficiaries of the proposed changes to the Performing Rights Act would not necessarily be hard-working session musicians, but rather the corporations who own the copyright on the recordings in question.

In hearings on Napster and digital downloading, members of Metallica argued that having control over one’s intellectual property is a moral right. Lars Ulrich described the intellectual property created by the entertainment industry as the United States’ “most valuable export,” and argued that artists should have freedom of choice over the method by which their music would be distributed. He argued:

I do not have a problem with any artist voluntarily distributing his or her songs through any means that artist so chooses. But just like a carpenter who crafts a table gets to decide whether he wants to keep it, sell it, or give it away, shouldn’t we have the same options? We should decide what happens to our music, not a company with no rights to our recordings, which has never invested a penny in our music, or had anything to do with its creation. A choice has been taken away from us. (U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary 2000)

Ulrich harnesses the notion that freedom of expression is an all-American value to imply that failure to act against illegal file-sharing places such values at risk. He later evokes the image of artists scraping by to survive, connecting to the notion that hard work and entrepreneurialism are American values. This rhetoric masks the real beneficiaries of the legislative action Ulrich is demanding: wealthy record labels who, in the 1990s, had increased the price of music beyond what the public was prepared to pay, and who were the gatekeepers to mainstream musical success (Knopper 2009). While Ulrich draws on Marxist tenets—that laborers determine the value of their labor—he speaks from a position of great means and as a beneficiary of capitalism and the music industry. He positions himself as a resistor and the company Napster as an oppressive force, even while he benefits from a music industry that exploits the labor of musicians.

At the same hearing, former member of the Byrds Roger McGuinn testified in support of online music distribution and file sharing, but used similar rhetoric, drawing again on notions of the rights of workers to determine the value of their labor. McGuinn, however, evokes the neoliberal model of entrepreneurship, which Moore describes as “a model of working based on organizing a venture on one’s own initiative and at one’s own risk. It is often presented as a welcome alternative to old-fashioned, hierarchical labor conditions—union shops in particular—and hailed for its ability to foster flexibility and innovation” (2016:35). McGuinn claimed that the internet allowed for the very freedom of choice that Ulrich claimed it curtailed, allowing artists both control over distribution and over their income, and that downloading services empowered creative workers to be entrepreneurial.

Numerous other artists, including Dan Navarro, Marty Roe, Anita Baker, Todd Rundgren, and others all make arguments related to artist compensation that depict musicians as a vital American labor force. In his testimony, Navarro outlines the process of creating a record, from composing, arranging, selecting musicians, recording, mastering, and releasing. He concludes:

One would expect that artists are paid handsomely for the level of talent and effort required, but that is not always the case . . . No matter what royalty arrangement I made with the label, or even when I produced my own albums, I never made a livable income from my records alone. So I wrote songs for other artists, sang as a background singer and instrumentalist for other artists, toured, and marketed merchandise. How ironic that after years of developing my skills and honing my creativity, I generate greater profits selling t-shirts. (U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary 2002)

Navarro, testifying on behalf of the American Federation of Musicians, again uses rhetoric that is characteristic in the way it argues for creative work to be recognized as labor. The secondary effect of these kinds of testimonies is that they help construct musicians’ personae as iconoclasts and fighters, who share the same concerns about economic security as many ordinary people. In other words, these testimonies help artists fit the ideals of authenticity that are valued in North American rock and pop.

In testimonies made by hip hop artists issues of labor and their connection to intellectual property are especially fraught. Hip hop is one of the most financially lucrative genres in the history of the American record industry; it is also a genre that emerged in underground communities and gave voice to experiences of marginalization, anger, and oppression (Kajikawa 2015; Keyes 2002; Rose 2008). Artist testimonies occur in the context of reception that has historically tied hip hop to racist myths of black criminality, reception which Perry ascribes to “the dispersed panic of citizens confronted by hip hop’s texts and arguments” (2004:107). The music expresses the very ethos of upward mobility and skepticism towards government that is at the heart of the discourse of the American Dream, but because the genre has its roots in African American culture, it has been a source of moral panic among some white audiences. Even so, the record industry takes advantage of the spirit of rebellion assumed to be at the heart of hip hop, in order to appeal to diverse, young audiences (Neal 2004; Negus 2004). The need to capture that ethos requires performances of authenticity from performers that manifest in, among other arenas, their political testimony.

When they testify before congress, some hip hop artists and executives argue that the genre truly exemplifies supposedly “American” values such as freedom of expression. Def Jam founder Russell Simmons argued against the practice of censoring records:

Hip hop music lyrics bear witness to truth of the social, economic, and political condition in our communities. I believe they must continue to tell the truth about the street, if that is what we know, and must continue to tell the truth about God, if that is what we found. Part of telling the truth is making sure that you know and talk more about and speak more about the truth than to appease those who are in power. Speaking truth to power is important, is essential. The Congress of the United States should not censor free speech nor cultural expression. It is unconstitutional for government intrusion or dictation concerning rating of music or limiting marketing that has the effect of denying free speech. What is offensive is any attempt by the government to deny the expression of words, lyrics, or music that emerge out of a culture that has become part of the soul of America. (U.S. House Subcommittee on Telecommunications and the Internet 2002)

Here, Simmons argues that the musical practices of black Americans should be recognized as central to American culture, and that the right to protest and freedom of expression be honored equitably. Of course, given Simmons’s role as a record company executive, it is also difficult to read this testimony without some cynicism: eliminating censorship would enable him to sell more records.

On questions related to music and piracy, hip hop artists again make arguments that rely on freedom of expression and freedom to profit as moral rights. LL Cool J and Chuck D offered contrasting testimonies at the same hearing. Cool J decried piracy and dubbed it “anti-American” (U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Investigations 2003). Chuck D, by contrast, recalled the history of black artists being exploited by the record industry and argued that black musicians were never protected by copyright law:

As an artist representing an 80-year period of black musicianship, I never felt that my copyrights were protected anyway . . . blues licks were taken from the Mississippi Delta without authorization so people could spend $180 to check out the Rolling Stones do it all over again. So the record industry is hypocritical and the domination has to be shared . . . [Peer to Peer file sharing] to me means power to the people. (ibid.)

Chuck D’s remarks get to the heart of the problem behind the idea that IP laws protect creators: they typically protect stakeholders with power, and not necessarily actual artists (ibid.).

Musicians’ testimonies about music use strikingly similar rhetoric about freedom and moral rights whether the speakers have industry clout, or claim to speak from marginal positions. These testimonies become part of star texts that construe performers as individuals invested in free, authentic expression. Furthermore, this rhetoric of American ideals—frequently invoked by Members of Congress themselves—is passed from musician to fan. This helps legitimate and perpetuate dominant cultural ideals.

Why testify? How testimony helps musicians shape their public image

In this section, we leverage foundational theories from study of political psychology and political communication to argue that congressional testimony helps prominent musicians, and other categories of celebrity, shape their public image in a positive manner.

Public attitudes towards musicians are unstable. Decades of public opinion research has shown that people do not walk around with firm, fully articulated attitudes about the world (Lodge and Taber 2013). Rather, public attitudes are unstable regarding almost every prominent actor and issue in society (Tesler 2015).[12] At any given moment, what determines whether the public’s opinion of a musician tilts in a positive or negative direction? It depends on the communication flow—that is, the mix of persuasive messages about an individual or idea in circulation at any given moment. Zaller (1992) argues that individuals form opinion statements through a three-step process. First, an individual receives a persuasive message on a topic, which may be positive, negative, or neutral. Second, the individual decides whether to accept or reject the information that they receive. Finally, when an individual is asked to state an opinion about a topic, they access recently stored persuasive messages—the ideas sitting at the top of their head—and relay an opinion that expresses the average sentiment. Empirical studies of Zaller’s argument find that people tend to uncritically accept the persuasive messages they encounter (Friedman 2014). As a result, opinion statements typically share two features: opinions are heavily biased by the ideas currently circulating in the communication environment and opinions reflect ambivalence as the communication flow contains arguments both for and against most people and ideas. In short, when people make opinions up as they go along, as Zaller shows they do, the considerations at the top of people’s heads dominate opinion statements. And because the dynamics of information exposure determine what tends to be on the mind of the public, attitude evolutions are due to changes in the communication flow.

Consistent with Zaller’s theory, we expect that, apart from self-identified fans, most people do not have strong or fixed opinions about individual musicians. For any musician, the public will access some negative and some positive considerations. On the negative side, Frantzich argues that the public will evaluate any high-profile musician who “work[s] hard to create and maintain their celebrity status” as “self-serving” (2015:115). Thus, the initial evaluation of any major musician will be one of ambivalence: an appreciation for the musical craft will be offset by the unattractive nature of celebrity itself. Further information about a given musician will do little to change this state of affairs. To illustrate, while most citizens know a fair amount about Lady Gaga, when asked to express an opinion about her, a typical American is still likely access a mix of positive and negative considerations—for instance, she actively uses her star power to expand LGBT rights but she also helps sexualize young women—and the resulting opinion statement is one of ambivalence. In summary, in a world with many considerations, most people end up with ambivalent attitudes toward musicians. In this situation, an influx of uniformly positive or negative information can produce rapid opinion change (and consequently a rapid change in the meanings of a musician’s star text).

Musicians work to increase the salience of positive considerations (Gamson 1994), so that the public relies on those positive considerations when forming an opinion. But this is not easily accomplished even for high profile musicians. Like all celebrities, musicians generally rely on the news media to get their message out widely. While they have social media, those who follow them are already positively inclined. The goal is to swing the opinions of the indifferent and the hostile. And to do that, they need the help of the mass media (Boykoff and Goodman 2009; Turner 2013). The problem for celebrities is that the media is not especially inclined to cover celebrities in the manner they wish to be covered.

All else equal, the media will focus public attention on considerations that paint musicians in a negative light. To understand why, consider the two major incentives that journalists and media organizations face. First, news organizations and their journalists build a reputation by breaking stories that other outlets do not have access to. Since celebrities and their press agents publicize any and all positive news items, the only way to distinguish one’s outlet is to break the negative stories that celebrities do not want out in the world. Second, most journalists work for for-profit media companies and need to write stories that command attention. Negative news attracts larger audiences than positive news (Soroka 2014). Consequently, to sell their news product, the media often emphasizes negativity, conflict, violence, and scandal (Dagnes 2011; Patterson 2013; Zaller 2005).

Since most musicians strongly prefer to focus attention on the positive aspects of their star text, they need to influence the information flow despite the motives of journalists. To accomplish this, they must create newsworthy spectacles that force journalists to include the musician’s preferred narrative in media reports. Testifying at a congressional hearing is one way of creating favorable news. The narrative of a musician interacting with the nation’s political leaders provides a spectacle with a compelling political message that is both entertaining and informative and, as a result, journalists will feel compelled to cover it (Warren 1986). Journalists cannot pass up the opportunity to show Alice Peacock singing “Bliss” to a room of senators or report Senator John Cornyn’s confession to Lyle Lovett: “My parents forced upon me trombone lessons. I learned how to play the guitar,” because “the opposite sex was not attracted to trombone” (quoted in Millbank 2007:A2). Furthermore, since congressional hearings are carefully choreographed affairs, there are no surprises or gotcha moments to generate negative news coverage. Consistent with this argument, we find that both political elites and journalists laud musicians for their contributions to congressional hearings. In nearly all cases, MCs greet musicians with enthusiasm and praise them for their policy knowledge and their advocacy effort.[13] For instance, after Billy Corgan discussed the technical details of performance rights policy, Representative Brad Sherman asserted: “You’re as good at this as people who do this for a living” (The Hill 2009). And Senator Joe Lieberman’s introduction of Kevin Richardson communicated the Backstreet Boy’s commitment and knowledge on the issue of clean water:

I know that you were born in Kentucky and raised on the edge of the Daniel Boone National Forest, and still own a farm there. You have family and friends throughout the Appalachian region. I understand that you are the founder and president of the Just Within Reach Foundation. Your foundation promotes personal responsibility and promotes environmental education, including the granting of scholarships. Finally, you have been involved in the issue before us today, and have flown over the coal fields in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee, so you have seen first hand the consequences of the granting of fill permits to allow the disposal of waste from mountaintop removal. Mr. Richardson is here as more than a well-known celebrity. He is knowledgeable on this issue and has in fact worked to protect the environment in his home State. I believe his voice will add to our understanding of the issue. (U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works 2002)

This positive reception extends to the news media, as we found by reading coverage of musician testimony in twenty-nine American newspapers for all hearings in our dataset.[14] For example, journalists praised John Legend for his “serious purpose” (Wehrman 2008:A3), Sheryl Crow for “speaking up” (Buckley 2008:B3) and Jewel for her “sincerity and knowledge” (Jackson 2007:O5). In short, musician testimony before Congress is a newsworthy event that generates positive media coverage.

Do audiences engage with musician testimony? An empirical analysis

The pervasiveness of celebrity political advocacy was once taken as “prima facie evidence that it might be performing some kind of social function for its consumers” (Turner 2013:26). However, recent scholarship suggests that many of the presumed effects of celebrity advocacy are muted or non-existent (Atkinson and DeWitt 2017; Brockington and Henson 2015; Markham 2015). Thus, in this section, we empirically evaluate whether audiences engage in the positive news coverage that follows from musician participation in hearings. Specifically, we draw on a new dataset of Internet search traffic to demonstrate that ordinary citizens actively engage with the performances of musicians at committee hearings on Capitol Hill. This evidence suggests that congressional testimony is a highly efficacious strategy for musicians seeking to shape their popular narrative.

In the previous section, we established that musician testimony before Congress generates positive media coverage. When citizens encounter these positive considerations, will they update their beliefs? Prior scholarship suggests that celebrity political advocacy does not lead to increased levels of policy engagement (Atkinson and DeWitt 2016; Thrall et al. 2008). This may be due to the fact that forming opinions about technical policy concerns is a tough analytical task. By contrast, we argue that it is easier for citizens to update their beliefs about a celebrity musician. Citizens do not need to sit through Sheryl Crow’s testimony to understand she is visiting Congress to speak about breast cancer. Sheryl Crow seeking increased funding for studying the environmental causes of breast cancer is enough to get people who come across this information to update their attitudes about Sheryl Crow. Therefore, we hypothesize that celebrity performance encourages a non-trivial proportion of the public to work at updating their beliefs about a musician.

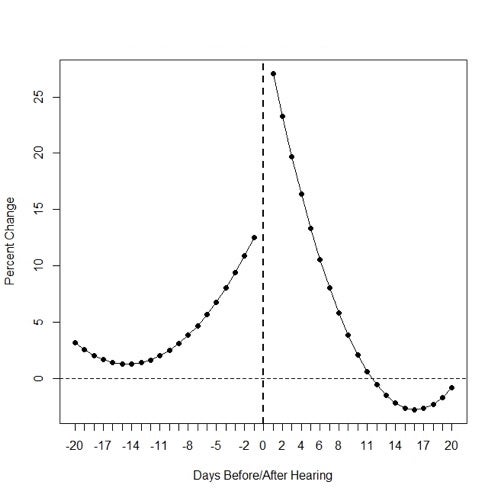

To empirically assess our claim that the public re-evaluates a musician’s image in light of their political advocacy, we leverage internet search traffic data. In particular, we measure daily views for a musician’s Wikipedia page just before and after a musician’s appearance on Capitol Hill. We use Wikipedia page views because scholars have demonstrated that is the first source that most people use when they begin to gather information and think about a person, topic, or issue (Höchstötter and Lewandowsky 2009; Laurent and Vickers 2009).[15] Our analysis is limited to musicians who have testified before Congress since December 2006, as Wikipedia search traffic is not available for earlier years. If testimony encourages the public interest in and engagement with a musician’s public image and narrative, then we should observe an increase in the number of daily views for a musician’s Wikipedia page immediately after she appears on Capitol Hill.

Before we can look for a spike in attention, we must determine how many views a musician’s Wikipedia page receives on a typical day—that is, we need to identify a baseline for the amount of attention that each musician receives around the time of their congressional hearing. We do this by calculating the average number of daily page views in the twenty days preceding a congressional hearing. We call this the pre-period. Then, for each of the twenty days prior to a congressional hearing (the pre-period) and each of the twenty days following a hearing (the post-period), we calculate daily deviations from this baseline separately for each musician as follows:

![]()

Thus, our variable—which we label “percent different”—takes the value 0 if article traffic for a musician on a particular date is identical to the pre-period average and would take the value 25 if traffic for a musician on that date is 25 percent above their pre-period average. If the process that we describe is taking place, then we expect that our page views variable will experience a spike in the days immediately following a musician’s appearance on Capitol Hill.

Does internet traffic spike after a musician speaks on Capitol Hill? And, if so, by how much? Figure 1 plots the predicted effect of a congressional appearance on a musician’s Wikipedia page views, based on the combined experience of all musicians who have testified since December 2006.[16] As the figure illustrates, Wikipedia page views for musicians appearing before Congress increase by 27% on the day following a hearing and this spike in interest persists for well over a week. This spike represents people seeking out information in response to how a musician is trying to define herself. These people are landing on the musician’s Wikipedia page with the idea that there is something to understand—they are trying to reconcile the issue at hand (say, causes of breast cancer and governmental assistance for research) with the person (Sheryl Crow). When these people read a musician’s Wikipedia page that policy issue is weighing on their mind. This is especially beneficial for musicians speaking on issues not related to music. Many of these individuals are involved with philanthropic organizations or have a long history of public service (e.g., John Legend’s Show Me Campaign, Elton John’s Elton John AIDS Foundation, and Usher’s New Look Foundation). This information is represented on their Wikipedia page and will be especially salient to individuals investigating a musician after their testimony. In short, this Wikipedia search data suggests that testimony is an effective means of getting people to resolve their likely ambivalent attitudes about a particular musician.

Figure 1: Effect of Testimony on Wikipedia Page Views

In Figure 1, we also observe a sharp spike in attention immediately prior to musician testimony. In our search of media coverage, we find that congressional hearings do not capture news coverage until the hearing has occurred. In advance of a hearing, knowledge of musician testimony is likely limited to those individuals who monitor the congressional hearing schedule, primarily D.C.-based congressional staff, interest groups, lobbyists, bureaucrats, and journalists. Thus, it seems that these individuals, in preparing for hearings, make an effort to learn about each musician prior to their testimony. That in and of itself is a huge victory for a musician as it helps shape their image among opinion elites. This, in turn, helps musicians gain access to future political events and assume positions of authority at those events (Cooper 2015; Rothkopf 2008). The end result of musician testimony may be that the news media and political elites start taking a musician seriously and that translates into the public picking up on the same cues.

Conclusion

Scholars frequently dismiss the content of celebrity testimony as irrelevant, trivial, or a hindrance to the political process (Demaine 2009; West and Orman 2003). Our analysis of these testimonies reveals, however, that a surface level reading misses the true power of such a testimony. They can introduce or eliminate critical voices from the issue definition process and can legitimize narratives for mass audiences—for better or for worse.

Beyond politics, these testimonies function as key aspects of musicians’ star texts, and have a measurable impact on audience engagement. They can push non-fans toward having positive evaluations of the musician. For instance, the advocacy efforts of high-profile musicians—which involve actions that go beyond music and are noted and discussed on those musicians’ Wikipedia pages—convey the impression that a musician cares about the cause more than their own career goals, and help fans and audiences develop a sense of investment in and personal connection to the artist. In essence, they help the artist perform authenticity. The impression of authenticity and realness, as the discourse about honesty, forthrightness, and “telling it like it is” that dominated the 2016 presidential campaign reveals, is something about which audiences care deeply, and which often motivates behavior.

In the same vein, musician participation in the political process helps to legitimize that process for audiences. When they testify, the musicians serve to help politicians. They enable committee members demonstrate that they are doing their jobs as representatives—a job that entails listening to and articulating a diverse range of societal interests. By inviting musicians, committee members appear to be inviting outsiders. But, as we have shown, musicians typically have strong ties to the interest group community in D.C. and proffer opinions that perpetuate dominant values and power structures.

When celebrity musicians raise their voices in the congressional chambers, they shape their images and narratives in the eyes and ears of audiences, they influence the way voices come to count in U.S. political arena, and they shape political conversations about music. We hope that future researchers can further evaluate the impact that these testimonies have for audiences, fans, and musicians themselves. Ethnographic work on public responses to musician testimony would illuminate how power flows among musicians, politicians, and the U.S. public.

References

[1] Our choice to channel Marvin Gaye’s “Can I Get a Witness” in the title of this article is in recognition of the many ways in which witnessing and testifying have served as crucial cultural practices not only in the legislative arena, but across contexts—including, in particular, in the musical traditions of Black churches, which influenced Gaye’s performances and songwriting.

[2] For instance, as Lincoln and Mamiya argue (1990), in the Civil War era, African-American Methodists defected from white churches and created new black churches as a means of testifying against the Southern rebellion (and Methodist preachers who supported rebels) and in favor of their vision of America’s constitutional system.

[3] For further exploration of the process of testifying before Congress, see LaForge (2010).

[4] Our timespan is dictated by the availability of hearing transcripts. To assess how musicians perform authenticity and how congressional audiences respond to these performances, we require full-text hearing transcripts. The United States Government Publishing Office has published full-text hearing transcripts for most hearings held since 1995. These transcripts are publicly accessible at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=CHRG.

[5] To identify witnesses affiliated with the music industry, we search through full-text hearing records in ProQuest’s Congressional Publications database, where each witness is identified by name and affiliation. For instance, Gretchen Wilson’s affiliation is “recording artist and GED graduate,” Nicholas Jonas’s is “singer, songwriter, and actors [sic],” and Usher Raymond IV’s “recording artist; Chairman, Usher’s New Look Foundation.” We searched for eight celebrity affiliations in the ProQuest hearings reports from January 1995 to January 2015. These terms include: musician, singer, recording artist, artist, entertainer, celebrity, and host. As a robustness check, we compared our list to Strine’s (2004) for the years 1995 to 2001 and we did not uncover any gaps.

[6] Because our interest is not in artists’ intentions in testifying before committees but in the ramifications of such testimonies for both the artists and political discourse, we do not conduct interviews with the musicians in question. As Gamson (1994) demonstrates, the celebrity image is an industrial or collaborative output representing the combined work of performers, those involved making a work of art (record producer, film directors, etc.), publicity, news media, agents, etc. Interviewing a celebrity is no great way of understanding the total meaning of celebrity in society. Brockington’s 2009 book Celebrity and the Environment is a case in point. Through interviews with celebrity conservationists, he finds that celebrities claim that they engage in conservation advocacy to do good. But Brockington finds that the true consequences of their political advocacy is to turn nature into a commodity—which has troubling and important consequences for actually conserving the environment. His interviews do little to contribute to his findings.

[7] Successful branding also depends on factors beyond artist and audience. For instance, Meier (2016) discusses how digital technology has caused changes in branding strategies. Moreover, musicians have played key roles in using their own brand identities to help other brands solidify their audiences (see further Love 2015; Lusensky 2011).

[8] Congressional testimony can influence both elite and mass audiences. While we discuss examples of both types of influence, our primary focus is on mass audiences. This is our focus because the question of how celebrities use political advocacy to gain access to elite audiences such as Members of Congress has received more attention in the literature (e.g., Atkinson and DeWitt 2017; Brockington 2014; Cooper 2015; Rothkopf 2008).

[9] In studying the relationship between popular culture and politics in the United Kingdom, Street, Inthorn, and Scott find that audiences judged musicians, but not other categories of celebrity, by whether they were “authentic” (2012:351), and that it was the perceived authenticity of a musician among audiences “that determined their ability to represent and/or speak for” audiences in the political realm (ibid.).

[10] In a similar vein, Ponte and Richey (2011) have shown that Bono’s development initiatives in Africa silence local actors.

[11] Helen Taylor (2010) argues that such remarks by Marsalis and others are central to post-Katrina discourse of cultural revival in New Orleans that has bolstered the city’s status as a tourist destination.

[12] Tesler (2015) identifies a small number of exceptions. These include partisan affiliation, racial issues, religiosity, and moral issues—as individuals develop fixed opinions on these issues during their pre-adult years. Stronger opinions can also emerge on individual issues (e.g., the U.S. invasion in Iraq) when opinion leaders send a clear and unified message.

[13] The only exception in our dataset is Backstreet Boy Kevin Richardson who faced negative comments from one United States Senator who disagreed with Richardson’s policy recommendations. Even here, Richardson received universal praise from all other committee members and publications like People gave Richardson a chance to defend his policy knowledge. On balance, the coverage was highly positive.

[14] We searched LexisNexis for a period of three days prior to a hearing and three days after. The papers we consulted include: Austin American-Statesman, Charleston Gazette (West Virginia), The Credit Union Journal, Daily News of Los Angeles, Dayton Daily News, The Free Lance-Star, The Hill, Hollywood Reporter, Investor’s Business Daily, Lowell Sun, The Maryland Gazette, Monterey County Herald, New York Daily News, The New York Times, The New York Post, The Philadelphia Daily News, Philadelphia Inquirer, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, The Record (Bergen County, NJ), Roll Call, The Salt Lake Tribune, San Jose Mercury News, St. Louis Post-Missouri, St. Paul Pioneer Press (Minnesota), Telegraph Herald (Dubuque, IA), The Times & Transcript (New Brunswick), Topeka Capital-Journal, Variety, and the Washington Post.

[15] Focusing on Wikipedia page views provides a few more benefits. First, scholars have access to raw Wikipedia page views—unlike most other search behavior. Second, this measure allows us to assess the impact of celebrity political advocacy in the real world as opposed to an artificial laboratory experiment, which may fail to capture real world dynamics (see Bennett and Iyengar 2008).

[16] Scholars have shown that persuasive political interventions have behavioral effects with a non-linear decay rate that approximates a quadratic process (see Lodge, Steenbergen, and Brau 1995). Following this convention, we model the page views variable as a quadratic function of time and a hearing indicator variable that differentiates the pre- from the post-period. We report the results of this analysis in our Replication Archive, which is available from the authors.