“We Gon’ be Alright”: Mental Health and the Blues in Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly

Art by Evan Sanders

Winner of the 2017 Lise Waxer NECSEM Prize

During the era of the Black Lives Matter movement, which strives to combat and expose the structural and personal oppressions of racism that impact the mental health of people of color, Kendrick Lamar released his message of self-love in his 2015 album, To Pimp A Butterfly (henceforth TPAB). In keeping with the Black Lives Matter movement, the album strives to combat issues plaguing the mental health of people of color, specifically Black men, regarding the cycle of gang violence and the power of self-actualization as exhibited in the rural and classic blues era. According to the blues tradition, the personal testimony of heroic tragedy is used to find a sense of belonging or, as noted Black novelist Ralph Ellison explained, it is “an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically” (Ellison 1992 [1945]:62). In a country that exploits, ostracizes, and oppresses people of color through systemic racism, Kendrick Lamar’s lyrical expression of personal heroic tragedy is an inspiration to process self-love while combating larger racial issues in order to truly belong in America. In this paper, I argue that the blues tradition is the primary entity that catered to Black people’s mental health and ability to survive the oppression that they faced in post-slavery America.

In order to understand the connection between Kendrick Lamar’s album and the blues tradition, I first define what mental health is and what it means to Black people historically. Second, I present the role of music in combating and managing mental health both during and after slavery as part of the Black public sphere. Third, I break the album TPAB down thematically along three themes that connect to the blues tradition: “To Pimp” (major lyrical statements and themes about systemic racism), “The Cocoon” (major lyrical statements, themes and content that relate to the blues tradition), and “The Butterfly” (major lyrical statements and themes that deal with knowing and empowering oneself to be proud and authentic). Lastly, I will connect the album, with its analysis of the blues tradition, to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Mental health has been, and continues to be, a complicated issue in the Black community due to the legacy of slavery. According to the collaborative work Lay My Burden Down by Harvard professor of psychiatry Alvin Poussaint and journalist Amy Alexander on suicide among Black males, Black people have historically been the subject of discrimination and experimentation by healthcare institutions. In response to this prejudiced treatment, Blacks have had to develop a stoicism and internal strength as a means to counteract the external biases they have been subjected to. According to Poussaint and Alexander, “many Black Americans view suicide as a sinful and cowardly response to the pressures of living. . . . Suffering through ‘the blues’ is seen as an expected rite of passage for most Black Americans” (2000:26). The acceptance of struggle as a part of the Black experience has caused Black people to keep their issues to either themselves and/or their family, and to self-medicate themselves with both positive and negative results. In some cases, Black people have relied on religion, faith, and prayer to deal with issues of mental health, while drug and alcohol use and other kinds of negative behaviors represent the negative paths toward self-medication.

In examining the role of religion and music in combating traumas impacting the mental health of Black people in America, Black music scholar Amiri Baraka explains that slaves believed that their healing would come from God and that God was the source of their freedom. This established Music as the medium used to create an emotional connection and release with God. He writes that:

The Negro church, whether Christian or “heathen” has always been a “church of emotion.” . . . Music was an important part of the total emotional configuration of the Negro church, acting in most cases as the catalyst for those worshipers who would suddenly “feel the spirit.” “The spirit will not descend without song.” (Jones [Baraka] 1999:41)

Music, since slavery, is a coping mechanism that Black people have used to release their emotions and manifest healing in their lives. This tool of processing suffering through music and strengthening a spiritual connection developed in the Black experience to form the blues after emancipation.

Post-slavery, Black people found emotional and spiritual freedom through the blues. According to Black theologian James Cone, in the blues, Black people shifted from their sole belief in God and instead embraced their reality. They embraced and shared their pains with the community to find strength and their greater humanity. The blues became a means of “secular spiritual” expression that, according to Cone, “are secular in the sense that they confine their attention solely to the immediate and affirm the bodily expression of Black soul, including its sexual manifestations. They are spirituals because they are impelled by the same search for the truth of Black experience” (Cone 1972:100). In bridging the secular and sacred worlds, Black people sought out healing by dealing with the pain through and with music. Political activist and scholar Angela Davis explains that “confronting the blues, acknowledging the blues, counting the blues, naming the blues through song, is the aesthetic means of expelling the blues from one’s life” (1999:135). The healing that people experienced came through confessing and confronting the blues. Healing was not sudden, but rather the blues gave strength to both individuals and the community, helping Black people to continue carrying the load. Kendrick Lamar’s TPAB connects with this historical trademark of perseverance in the blues tradition and the larger Black experience.

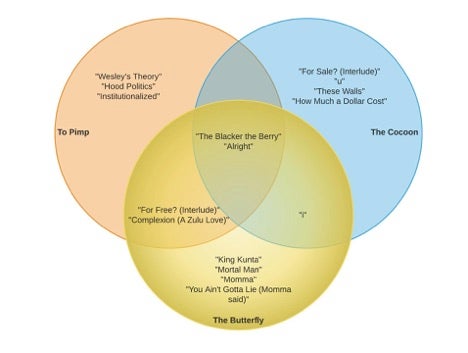

Lamar’s album connects to the blues tradition through its themes of secular spirituality, injustice, depression, and resentment. In fact, these themes are processed under situations of structural racism that lead Kendrick Lamar to examine himself and reaffirms his self worth. My categorizing format of “To Pimp” (structural racism), “The Cocoon” (self-examination), and “The Butterfly” (reaffirmation), is a tool that I’ve used to visually group the songs and to understand how Lamar’s songs overlap according to these themes. In breaking the album’s songs down into these three categories, I’ve selected four songs that exemplify themes in relation to the blues tradition: “Institutionalized” (To Pimp), “U” (The Cocoon), “i” and “Alright” (The Butterfly)(See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Diagram shows author’s categorization for Kendrick Lamar’s TPAB, dividing the album’s songs into three categories: To Pimp (Structural Pitfalls) in orange (songs with lyrics and themes about systemic racism), The Cocoon (Blues) in blue (lyrical statements, themes, and content related to the blues tradition), and The Butterfly in yellow (lyrical statements and themes that deal with knowing and empowering oneself to be proud and authentic). Several songs are shown with overlapping lyrical content and themes.

To Pimp: Major Lyrical Statements and Themes about Systemic Racism

In the song “Institutionalized” Kendrick Lamar describes his personal struggle with his rap image, one rooted in his traumatic upbringing in Compton. Kendrick Lamar is not a member of any street gang in Los Angeles. By association with his friends and family, however, he is involved in the craziness of the “m.A.A.d. city” called Compton. Living in Compton meant that he has absorbed years of traumatic experiences, as told in his 2012 album good kid m.A.A.d. city; however, in TPAB he is removed from the Compton setting and he faces the struggle of healing from his traumatic past. In the introduction to “Institutionalized,” he introduces this struggle in lyrics written in the traditional bluesy AAB lyrical style:

What money got to do with it/ when I don’t know the full definition of a rap image?/I’m trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it/Institutionalized, I keep runnin’ back for a visit/ Hol’up, get it back/ I said I am trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it/ Institutionalized, I could still kill me a nigga, so what?

Kendrick is struggling to shed his old habits of survival in the ghetto as he is seeking to define his rap image. He raps, “My defense, mechanism tell me to get him/ Quickly because he got it.” Here he expresses the need to steal items that would make him look more like a stereotypical rapper.

This habit to steal, for status, comes from a lack of economic opportunity to earn, which is a structural limitation of poverty that drives people to be divisive towards their community. According to Black sociologist William Julius Wilson:

In the context of limited opportunities for self actualization and success, some individuals in the community, most notably young Black males, devise alternative ways to gain respect that emphasize manly pride, ranging from simply wearing brand name clothing to have the “right look” and talking the right way, to developing a predatory attitude toward neighbors. (Wilson 2010:18)

In these communities of limited opportunities, people participate in street gang activity in order to gain respect and status, often through violence. Accordingly, Kendrick Lamar’s personal experience of gang violence while growing up in Compton, where violent interactions by Bloods and Crips dominate the community, has impacted his emotions and psyche negatively.

In his most recent song “Fear” from his 2017 album DAMN., Kendrick evokes his seventeen-year-old traumatized emotions and psyche when growing up in Compton:

I’ll prolly die walkin' back home from the candy house/ I’ll prolly die because these colors are standin' out . . . I'll prolly die from one of these bats and blue badges/ Body slammed on black and white paint, my bones snappin.'

These feelings of hopelessness caused by Compton’s hostile environment are connected to the lyrics “to kill” and “steal,” from the song “Institutionalized.” They highlight the negative consequences of exposure to Compton’s hostile environment that have caused him (and others like him) to experience internalized negative emotions and have further manifested these emotions as violent behaviors.

Similarly, in the blues tradition, blues artists dealt with and confessed their own struggles with external and internal violence. Blues men and women developed their art in the Jim Crow era, where lynching was a common traumatic experience, and in Jook Joints, where they carried knives and other weapons in preparation for self defense (Gussow 2002). Under these conditions, blues men and women were institutionalized to internalize violence. For example, Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” paints the horrific imagery of lynching:

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck/For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck/For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop/Here is a strange and bitter crop.

The depiction shows the deep violent impression that Billie Holiday receives about the worth of Black lives as objects for violence and murder. Billie Holiday’s expression of this reality to an audience of white listeners is bold, dangerous, and necessary for the survival of Black people, much like Lamar’s expression of the negative impression Compton has on him is necessary for the survival of Black people.

The Cocoon: Major Lyrical Statements, Themes, and Content that Relate to the Blues Tradition

In the song “U,” Kendrick lashes out his resentment on himself. He exhibits an episode of depression, anger, and suicidal thoughts that growing up and leaving Compton has had on him, especially as a rap artist. He feels resentment towards himself for not being able to influence his family and friends, like his fans, to live a better life when he says,

You preached in front of 100,000 but never reached her/I fuckin’ tell you, you fuckin’ failure/you ain’t no leader!

This links back to the blues through the process of confession to expel the blues. When he says, “loving you is complicated,” he is acknowledging all the self-hate stored inside. This process allows him to come to terms with his humanity.

Black feminist writer and social activist bell hooks states that, “Black males are responsible for the manner in which they confront those sorrows or fail to do so. Black males then must hold accountable when they betray themselves, when they choose self-destructive paths” (hooks 2004:137). Kendrick Lamar, in exposing this dark moment of his life, is taking responsibility for his humanity— something that Black men are not traditionally taught to do while learning to perform their masculinity. In hooks’ book, We Real Cool (2004), she looks at how masculinity is often driven by the need for money, to be seen as brutes and to repress our feelings. “U” deconstructs those ideas. Confronting his failures and self-destructive behavior, Kendrick is able to move forward and say that he loves himself.

The Butterfly Major Lyrical statements and themes that deal with knowing and empowering oneself to be proud and authentic.

“i” is the climax of the album, symbolizing “The Butterfly,” with its resolution of the tragic journey that Kendrick Lamar took to love himself. Throughout the song, there are major lyrical statements and themes that deal with knowing and empowering oneself to be proud and authentic. For instance, Kendrick Lamar de-feminizes the human traits of love and empathy, which in Hip hop culture is feminized. According to bell hooks,

Recognizing the meaning of self-actualization requires an understanding, and, on the other, appreciation of the need to nurture the inner life of the spirit as survival strategy. Any Black male who dares to care for his inner life, for his soul is already refusing to be a victim. (hooks 2004:149)

On the album version, “i” is a live recording of a performance that ends with inspiring words of self-knowledge about the N-word:

N-E-G-U-S description: Black emperor, king, ruler, now let me finish/ The history books overlook the word and hide it/ America tried to make it to a house divided/ The homies don’t recognize we been using it wrong/ So I am break it down and put my game in a song.

Kendrick defends the word by revealing its original Ethiopian root word: “negus,” meaning royalty. The importance of this knowledge for Kendrick Lamar and the Black community is the reclaiming of all their tragedies. A word that was used to dehumanize Black people is exposed to become a word to empower Black people. Blues is about taking control of your situation and understanding yourself deeper. Cone recognized this as well, claiming that “insofar as the blues affirms the somebodiness of Black people, they are transcendent reflections on Black humanity” (1972:113). Through “Negus,” we understand that we are somebody and that affirmation of humanity is critical in the fight for Black lives. Black lives have to be saved through loving ourselves, healing our personal internal issues, in conjunction with fighting larger systemic issues. This perseverance to transcend tragedy is further exhibited in the most well-known song of the album, “Alright.”

“Alright” is the song that moves beyond Kendrick Lamar’s personal tragedy, directing his words to be relevant to the larger context of the Black Lives Matter movement. According to Cone, “The important contribution of the blues is their affirmation of Black humanity in the face of immediate absurdity” (Cone 1972:114). “Alright” is used as a protest song that affirms Black humanity in the context of police killing:

Wouldn’t you know/We been hurt, down before/Nigga, when our pride was low/Looking at the world like. ‘Where do we go?/ Nigga, and we hate po-po/ Wanna kill us dead in the streets fo sho’/Nigga, I am at the preacher’s door/My knees gettin’ weak, and my gun might blow/But we gon’ be alright.

These lyrics acknowledge years of collective struggle and our perseverance through those struggles. Kendrick understands the killing of Black men by the police to be another hurdle in the Black experience that can be overcome through spiritual strength to survive (the preacher’s door). At the preacher’s door we confess our struggles and expel the blues from our lives that harm our bodies (My knees gettin’ weak). The internal oppressions that our bodies absorb from the traumatic experiences of our lives (my gun might blow) give us the strength to say that “we gon’ be alright.”

Despite this profound blues message of Black determination by Kendrick Lamar, people found issue with Kendrick Lamar as an artist for the Black Lives Matter movement. According to music journalist Jamilah King, Kendrick Lamar had a contentious relationship with a Black Lives Matter activist because of his statement about Ferguson. Kendrick, in an interview with King, stated:

I wish somebody would look in our neighborhood knowing that it’s already a situation, mentally, where it's fucked up. What happened to [Michael Brown] should’ve never happened. Never. But when we don’t have respect for ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us? It starts from within. Don’t start with just a rally, don’t start from looting--it starts from within. (King 2016)

Kendrick Lamar wasn’t blaming Black people for their plight; instead, he was trying to get them to understand what his personal tragedy taught him: that personal evolution is possible. In other words, “‘Alright’ is the song that tells people evolution is OK, if not natural and necessary” (ibid.). As a person that was able to transcend his traumatic past in Compton through examining his own internal oppressions, Kendrick was able to evolve to be an example for his community. This process of evolving is what the blues tradition is about. We wrestle and confess our struggles to give others the permission to do the same. Our humanity as Black people comes from that collective understanding that we depend not only on ourselves, but also on each other, so that we can say “We gon’ be alright.”

As Black people, our humanity has been debased by countless historical and modern day traumas. Despite that reality, Black people (and in this case, Kendrick Lamar) have been able to survive and find a way to evolve past their personal and collective situations of struggle. According to music journalist Carvell Wallace, “Kendrick makes the kind of music that can lead you to fight for your own survival. He is not a savior or a leader, as some have attempted to cast him. He is a man who can flow” (Wallace 2015). In other words, Kendrick’s flow is the blues tradition. He is one of the many modern rap artists that boldly and honestly tell their stories to redefine Black masculinity and the Black male rap image, and to destigmatize issues of mental health in the Black community. Earl Sweatshirt, Kendrick’s favorite contemporary rapper that also talks about mental health issues in his songs, highlights the defining feature of Kendrick’s music in this statement:

I’m still so thankful for his position because he’s doing that work so that fools like me can still find myself. I just don’t do it in the same way as Kendrick. Kendrick is so explicit in the way that that nigga writes...it gives me room to find myself. (Khoury 2015)

Kendrick’s confession of his personal story against depression, resentment, suicide and survivor’s guilt led him to a greater understanding of himself. For others that are seeking to deal with their own situations of despair and to reach a greater understanding of themselves, Kendrick gives them a model to affirm that their lives truly matter.

References

The Lise Waxer NECSEM Prize

The Lise Waxer NECSEM Prize is an award for the outstanding undergraduate student paper presented at the annual chapter meeting. Lise Waxer was a Canadian-born ethnomusicologist. She conducted extensive research on salsa music and its Cuban roots and completed doctoral studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Waxer edited Situating Salsa: Global Markets and Local Meaning in Latin Popular Music, a collection of essays on salsa in global perspective. This award honors her memory as a distinguished teacher, scholar, musician, and colleague.